This is a two-stranded sequence of letters. One strand concerns the key techniques of kiln-fired stained glass painting.. The other strand — this one which you are reading here — concerns restoration.

Should you be joining this sequence late, it might benefit you to know that, whilst outside I am gruff and wildly rancorous of our times, inside me — deep inside, where my inner child yet frisks and gambols with the innocence of a new-born lamb — that’s how I also am, just not quite as woolly.

Previously on restoration …

Hang it, I’m in no mood to repeat myself for late-comers or amnesiacs: to get the series catch-up, see here and by all means join us when you’re up to speed.

In the studio where I first worked — (“Goodness me, he’s off again: let him have his rant, he’ll soon calm down”) — the through-put was frenetic and I dare say unscrupulous.

Huge, innumerable crates of disintegrating stained glass windows bought allegedly at auction would arrive in dubious unmarked vans on Monday.

By Friday these windows would be stripped, cleaned, painted, re-built to vastly different sizes, and polished so they gleamed like gun-metal; or, if this hadn’t happened, it would be claimed there was no money to pay the wages.

Just like in repertory theatre — where a group of actors assembles for the summer season and each week learns a new play to perform the following week, whilst every evening these same actors perform the play they learned the previous week — terrible mistakes will always happen in response to undue pressure: imagine rehearsing Macbeth by day whilst playing What the Butler Saw by night.

Oh yes, you recover and laugh off the errors afterwards, but nothing can make the errors good again, not even when the sun explodes and everything has turned to dust.

Here’s an example which although it was not an error that I myself committed — my sins lie over the seas and far away — is the kind of horrible mistake which easily occurs with stained glass restoration when you are pushed for time and agitated for loss of wages:

I’m ashamed of my participation in debauchery like this when I was training. My hope is that an early life of crime can sometimes be atoned for by years of penitential thought and also — what might be more important if self-delusion doesn’t cloud the judgement, but yet I fear it always does — action.

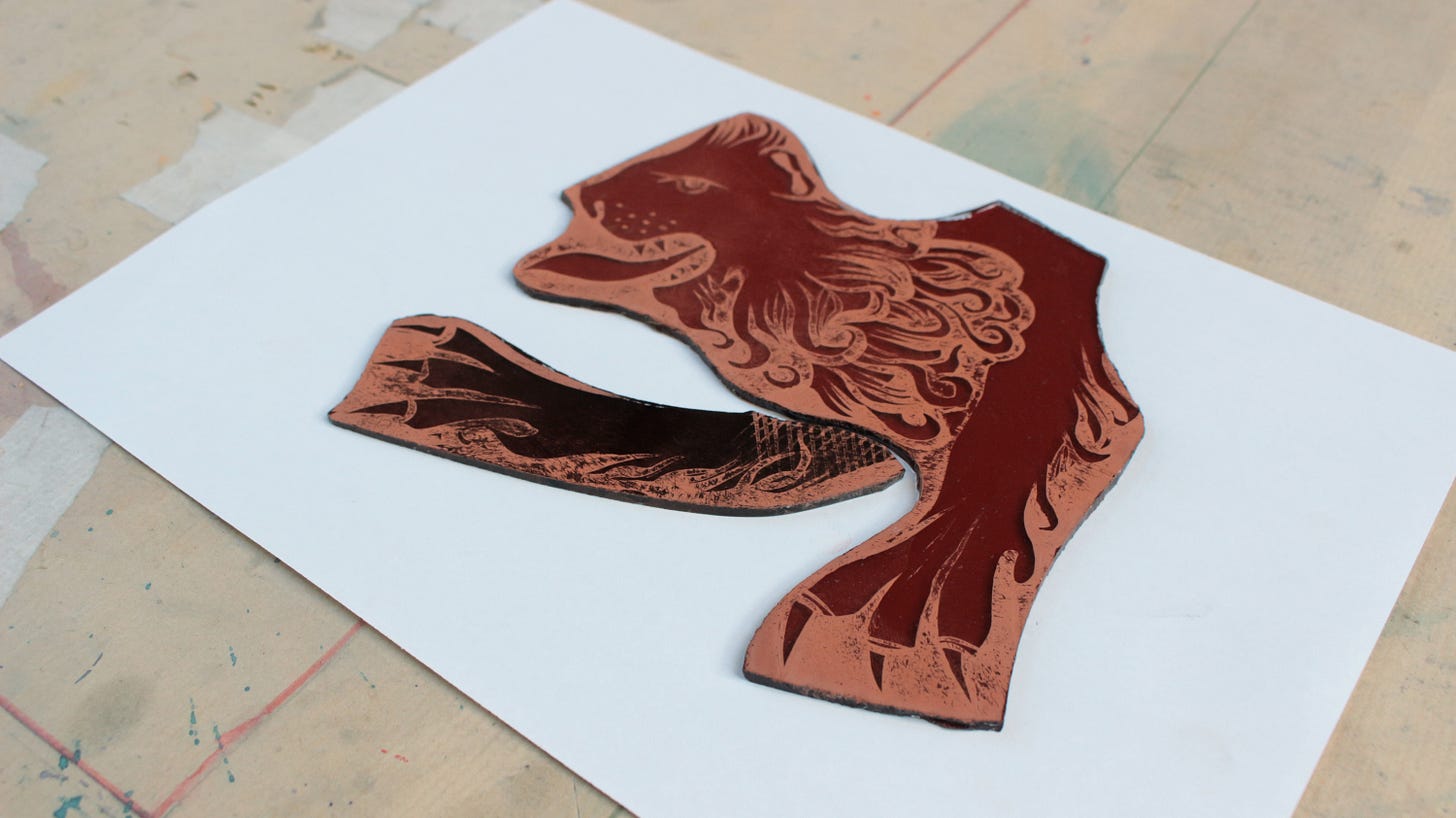

Speaking of action, there’s some freshly cut red glass which is just gasping for a lick or two of paint:

Now, much like the repertory actor, the seasoned restorer must be ready to play a thousand different parts and decline those roles which are outside his competence.

I do not mean to allege we have succeeded, just to set the bar.

Also, I wish to offer counsel.

Of all the ambitions which people have confessed to me by email these 15 years in which I’ve written letters to you, the ambition to restore stained glass ranks highest by a long way.

My counsel always is: become proficient in as many different techniques as time allows you.

The reason?

When they are scrutinised, we find that many different styles of stained glass painting will largely decompose into different combinations and orderings of those techniques.

Thus, even when you can’t be certain of the original combination and ordering, you might yet know enough to imagine a combination and ordering from your accumulated resources which will deceive your audience in a way that is legitimate.

And you would then take pains to prove your hypothesis through experiment, because, unlike the young criminal in the previous section of this letter, you’ll make the time to do so.

As for money: you’ll have to find your own way there. Ourselves, we generally went without those items which others take for granted. I promise you that it seems worth it in the end …

… though that will also be a matter for your own judgment when these letters reach their natural finish.

But even should you disagree, the fire inside me will not be quenched, nor my soul cast down. For when I chance to meet some contemporary of mine from Oxford or the City — wealthy, self-satisfied, and dead of eyes —

… I appreciate how great has been my fortune that I escaped a fate which was one-time certain to be mine.

This combination isn’t difficult. First I’ll show you pictures because, when you watch the video, then you’ll already know the sequence, so I can rant about extemporise on wider points.

We have the glass. We also have the drawing, whose development I recounted last time:

(The criterion for a drawing: good enough to guide the glass painter. What other people think about the drawing is neither here nor there. Yes, sometimes we must sell dreams to clients, but what really matters is your painted glass’s beauty.)

Once you’ve cleaned the glass, you pick and choose from the techniques you know, and then assess where they have taken you.

We began by copying from the design in order to outline the shape and block in around it:

Note that when we paint, one hand holds the bridge (whereas when we use a stick to highlight, also from the bridge, one hand holds the glass). What you do is up to you. I simply draw this fact to your attention.

The brush is a da Vinci 5519. It takes a bit of practise getting used to and there’s a special way of loading it (you sink and swirl its belly in the paint) which I promise you we’ll talk about another time. It’s excellent for dynamic flicks and also speed. But speed isn’t everything it’s cracked up to be. There are times when it’s expedient, despite the risks, to swap one brush for another:

(Take care whenever you elect to do this. It’s not unlike the feeling of changing one violin for another mid-performance. Even professionals need time to adjust to their new circumstance.)

Which brought us here:

(It was particularly with the cross-hatching that the traditional tracing brush came into its own.)

Next, since it was an ancient lion that must be forged, we used an old tough painting brush to kick the c**p effect a dry stipple:

Which brought us here:

Now I cannot remember if we ever speculated this might be enough mistreatment to age our lines; but I’m sure we foresaw there’d be a problem remaining to be solved concerning tone.

That is, most of the original glass had been lightly undercoated, but most of this early wash of paint has disappeared now.

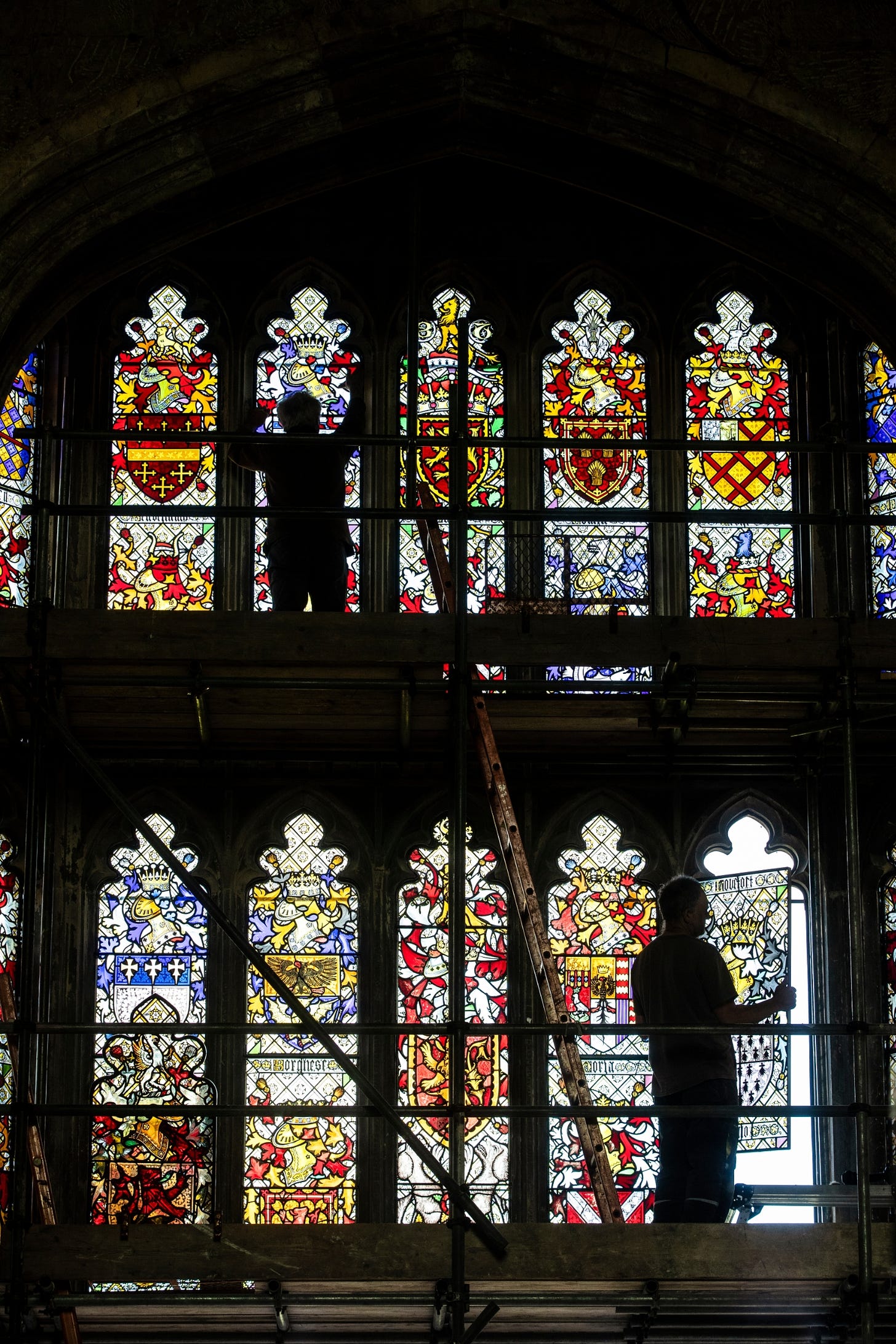

Therefore we judged our challenge was, not to replicate what was there originally — we could not ever work it out — but to copy what remains, so that, for instance, our new lion would be required to look and feel much like the other lion which sits above with far-degraded tone.

Here’s the shield before we started work on it:

As it happened, we saw immediately that more abuse was needed to our new lion; also that it would be hugely beneficial if somehow we could add just the faintest hint of tone.

That’s why we now turned to a different medium than the water and gum Arabic we’d used till now: Propylene glycol.

First of all, we applied a wash of glycol paint on top:

This softened the dried paint and also introduced a veil across the glass.

Then we pursued some gentle blending:

Lastly, some serious rough treatment, to erode the lines and also to remove a significant quantity of wash from the unpainted areas of the glass, but crucially not all of it. If you want a name for this technique, it’s known as a wet stipple on steroids. (Say this to a professional glass painter, and she’ll give you a secret handshake in return.)

You see, we used the round badger to really beat the painted glass in a most uncustomary way, which brought us here — you can detect the last remnants of the glycol wash:

Now was this close enough to the surviving lion?

If this had been the last step in the restoration process, I don’t judge it would have been. But what we knew was that, once the whole window had been restored and re-leaded …

… then nearly everything would be painted on the back with glass paint mixed with gold size as you see has happened here if we allow ourselves to jump forward to the end of time:

(Bottom-left, the latest paint’s still drying.) In other words, we knew there was a process yet to come which would improve the appearance of the original lion (the top one) and also give us the opportunity to make our lion (the bottom one) appear similar enough. Therefore we fired our freshly painted fakes …

… and then moved on to other work. By this time we’d restored a sufficient number of the other windows in order to be confident that everything would be fine. And if it weren’t fine, the worst was only that we’d have to remove the replacement and work some more on it. Fortunately, when the stakes are high and you are working virtuously in order to make atonement for your earlier sins (however innocently committed), you learn to pay attention and only commit a few mistakes.

You can try these steps on any design you wish and thereby experience what the sequence feels like. I wager you’ll find it’s strange to damage those same lines which you recently traced with care.

But I don’t think it’s the worst feeling you might feel.

We once had to take a hammer to a set of skylights that we’d made, and then repair them. Imagine what it feels like to paint this face and hit it and then repair it with copper-foil:

And no, you don’t get to cut the glass, because cutting just won’t look real enough. You have to hit it. I promise you, you’ll cry out. We did — grown men both of us, and we cried out, alone in our studio, and pathetic as a mother cat whose kittens have been taken from her. But our client paid us to take the authentic aging process to this extreme. And who were we to argue with his bodyguards, who, come to think of it, bore a strange resemblance to the drivers of those unmarked vans which arrived each Monday at the studio where I first worked.

Even after all these years I can’t help but wonder what became of them.

A sudden gust of cold air in summer leads me to think that I must double-down on my atonement.

Now I know I promised you a rant but I judge I’ve said enough today. I therefore hope the video on its own, coupled with the words you’ve read so far, will be enough.

One brief note: when painting and distressing the new lion, the pieces of the old lion are always on the light box for comparison.

May God help keep our spirit bold when we are put to trial. Until the next time, a fortnight hence.

Rants are good. Rants are our friends. As long as they're aimed at the right targets, they can accomplish many things. But I do have a question about the general topic here, the artificial duplication of age-related deterioration on old painted glass. Having taken your original class and learned about stippling and "spottling" (a word I love) I became adept at creating an antique look. But the actual paint fired into the glass froze a moment in time, that replicated the appearance of a worn piece without duplicating the actual surface condition, which can only be created by Time acting on the original paint through weather, sunlight, wind, airborne dust, cleaning, and so forth. So am I fooling myself about the long-term viability of artificial aging? If I put a repainted piece like your lion into a window that has an original just like it, as yours does; and if my applied artificial aging is ever so perfect in appearance today; will it still look like its original neighboring piece a hundred years from now? It seems unlikely that such dissimilarly-worked pieces will be acted on in the same way by Time's aging forces, and that bothers me. I know there's no practical way to duplicate the original piece and somehow accelerate natural aging forces, and we have to do the best we can to replicate the appearance today, now, this moment in time. But does it ever worry you that this beautiful and tricky matching will be exposed in future generations, and will have to be done over again to bring it into alignment with whatever Time will have done to the original piece?

I so look forward to your rants Stephen - they make my fortnight 😊 The magnitude of the commission could be daunting on first appraisal, but I guess it’s one of those projects that, in the words of my ethnography conservation tutor, is done ‘like eating an elephant - one bite at a time.’ I may have missed a bit in the explanation, but I wondered what the final details post-leading are done for and with please... to even up some parts with the top lion? Also, it can’t be fired again at that stage, so I’m guessing it must be encased behind another layer of glass for longevity?