The last time I wrote to you about restoration — that was four weeks ago now — you saw with your own eyes how the window and its companions were in a sad condition:

Today we can consider the different kinds of intervention which could bring these windows back to glory.

This letter is a bird’s-eye view, a whirlwind tour. In coming weeks and months we’ll double back and spend time at every stage.

All I want today is that you might see the journey’s landmarks.

Once we’ve made a plan, and only then, ours is a journey which likely starts with stripping down a window or part of it. This will be because the lead has failed or because it is the best way for you to conduct other repairs:

This will leave us with a disassembled but carefully laid out jigsaw:

We might now repair some of the broken glass by means of glue:

Or, later on, copper foil is another option for visually important breaks:

Or a fine lead:

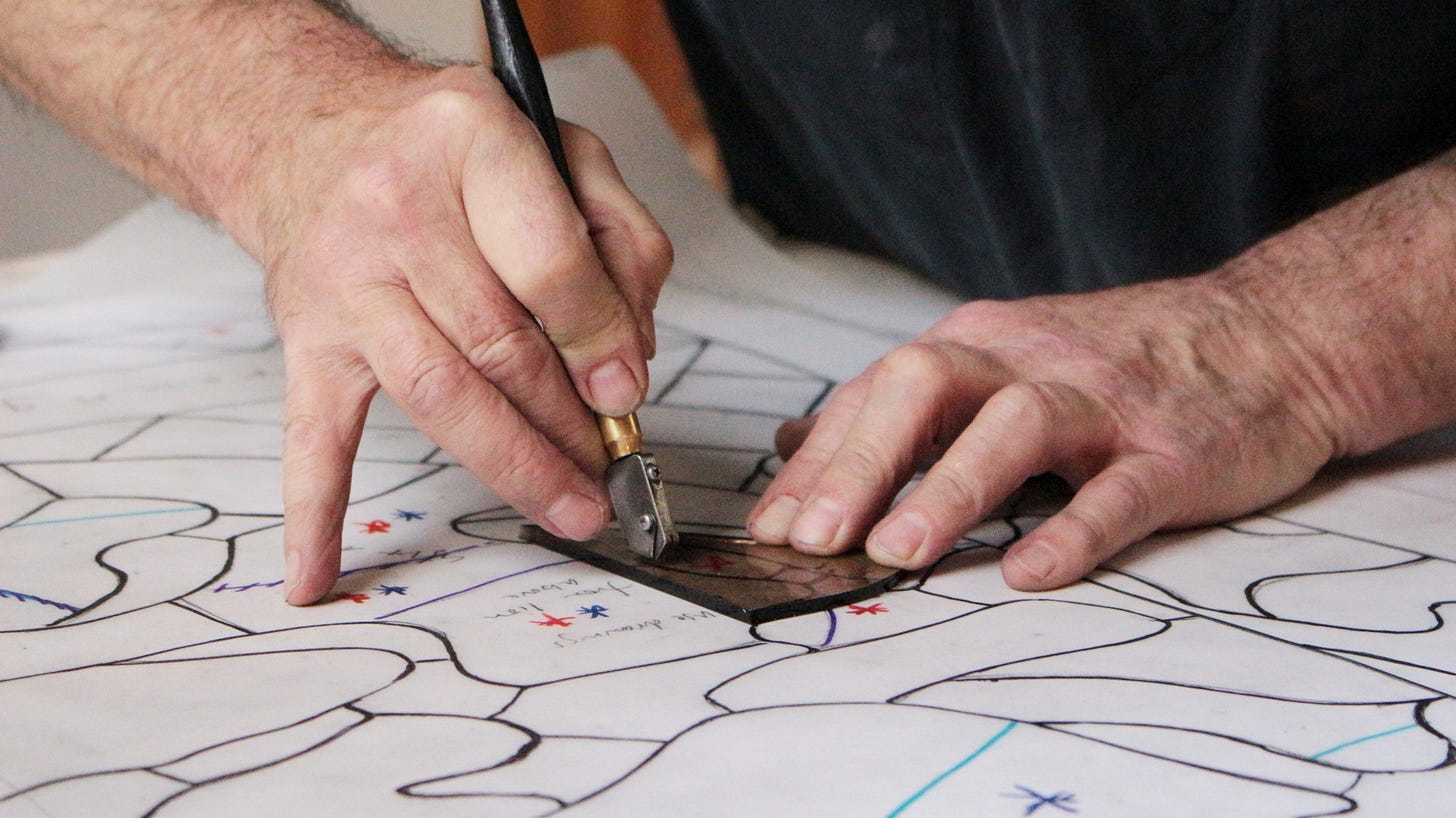

We’ll likely need to cut replacement glass:

There could be various reasons to do so.

For instance, the damage could be too bad to fix with glue, copper foil or fine lead:

Or the original glass might have fallen out and smashed:

Or perhaps because someone has fitted bad glass during an earlier attempt to repair the window:

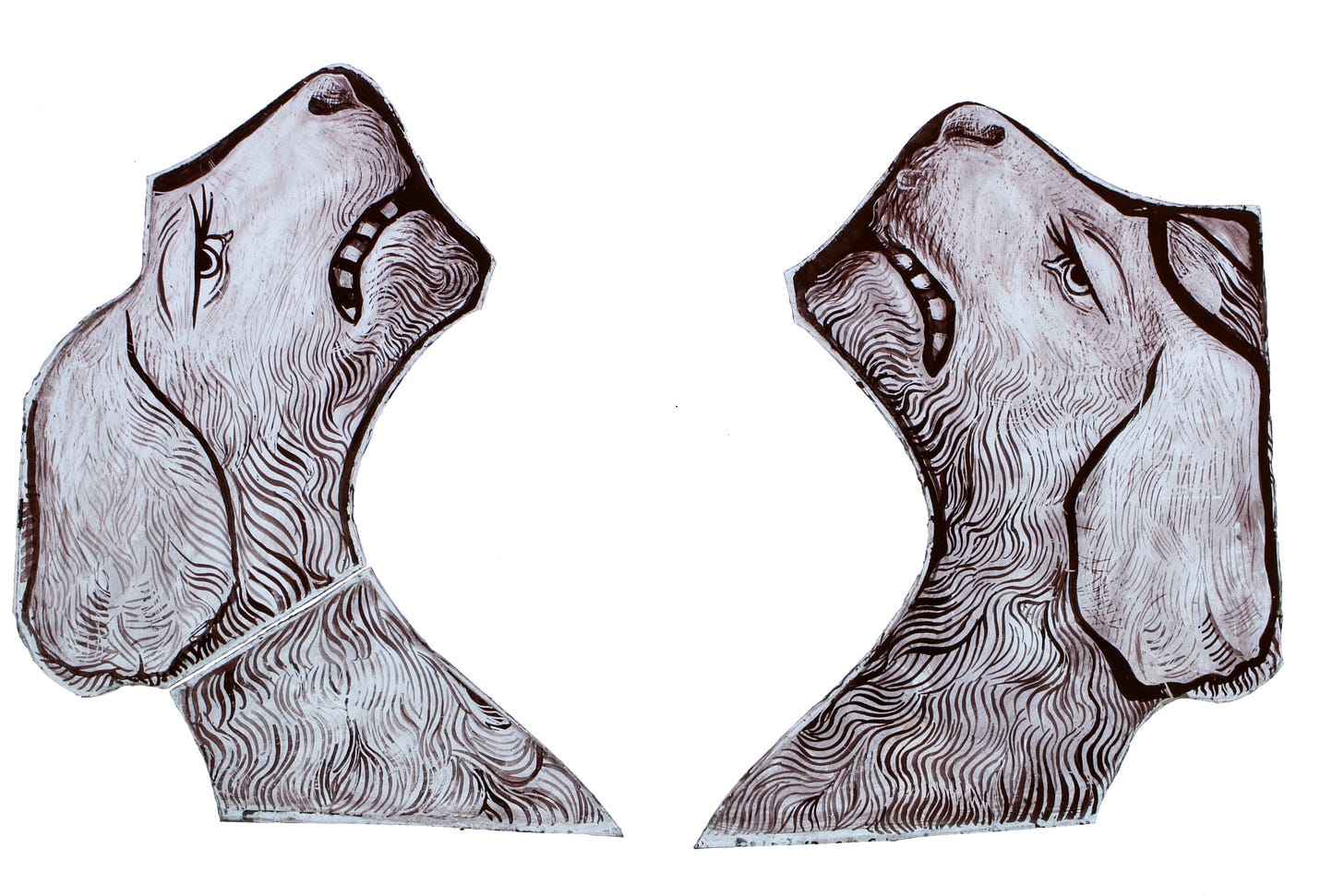

There, in the lower lion, the repairman didn’t even paint the ugly glass. Perhaps it’s just as well, for which is worse? — Not repainting painted glass that’s disappeared, or repainting it badly like these two dogs:

The fact that the effect is comical does not lessen the offence:

Arguably, ugly unpainted glass at least prevents the rain from getting in — it could have been the best glass there was to hand; whereas badly painted glass might suggest we have a perplexing lack self-awareness, like the innocent who whistles during Barber’s Adagio for Strings, and ruins it for everyone. Anyway, we decided to repaint the comic dogs. You can watch the process here:

It might seem obvious to repaint the comic dogs but in fact it’s controversial: would you imagine there are those who argue that an earlier repair, however crass, should be conserved?

Of course you would. It’s 2023. The world’s gone mad. You know full well that clever people sometimes believe dumb things because they’re great at reasoning to bad conclusions. They don’t know how to stop themselves. So greatly do they esteem their own capacity for logic, their credentials spur them on to ever wilder mind-spun lunacies. (The “knowledge economy,” anyone?)

The wonderful thing about learning something practical, however, is that errors can be noticed early on.

Whether those errors are put right is a different matter altogether. I found this window in a pretty, ancient English church where the worshippers were too kind to say a word against the priest who sanctioned it:

It gets worse. This horror was one of a pair. Be thankful I will spare you a description of the four quatrefoils which perched, lurched and squatted above them.

You have to plan and practise whatever it is you intend to paint. (See, above, what happens when someone doesn’t. I’ll bet my sainted badger blender those windows weren’t worked out on paper first.) Therefore, new glass will mean new drawings:

Lots of new glass thus means lots of new drawings which, if you’re in the mood, you can undertake in batches, each batch lasting several days:

Remember, we’ll return to these steps in the coming weeks and months, and give each one of them the attention it deserves.

Then comes that moment the glass painter has trained for — painting, and lots of it …

… in whatever style and sequence of techniques is necessary:

When all the newly repainted glass is fired, it’s a good time to put the window back together:

Solder it:

And make it strong and weather-proof:

But this leaves an urgent question: how is the failed paint to be restored?

In this country, there’s a rule: if you intervene, you must be able to undo and take your intervention back. Actually, it’s a rule of thumb: you also have to use your common sense.

Thus, common sense agrees that, if the lead is failing, it’s alright to strip and throw away the old lead. (Eco-warriors, calm down: “throw away” is just a useful way of speaking.)

Common sense also agrees you can’t repaint and fire ancient glass because that would take you to a place you can’t step back from.

This leaves repainting and not firing, for which you’ll need a medium which dries hard enough to last for years but which yet could be removed, if you chose to, without damaging the painted glass.

“Not on the front,” I’m glad to hear you say.

Quite right, it can’t be on the front. The original paint is already failing. It would likely suffer more from any medium that stuck hard enough to last for years.

“Nor on the back,” you also wail. “The vile English weather will wash it away in just one summer.”

Whilst I maintain that’s somewhat mean-spirited of you, I grant your general thrust: the weather would wear it off … eventually.

The answer is, therefore, somehow to protect the outside freshly painted but unfired face.

Thank goodness, therefore, the Victorians themselves had double-glazing.

See, there are two rebates here:

The inner rebate was where the painted stained glass originally went; the outer rebate took its original protective glazing.

Therefore we can re-lead the window and then, after all the vigour and wetness of cementing, paint it with a special medium on its back, thereby creating the impression that the original though faded paint remains as strong as ever:

Then we leave the window flat, and wait for the medium to dry:

To summarise:

Strip.

Repair e.g. with glue, copper foil or fine lead.

Cut new glass.

Paint new glass in the required style.

Re-lead, solder and cement.

Restore by painting on the back.

This is an outline. It’s roughly how we imagine we’ll get from there-on-the-left to here-on-the-right:

But, short of a piece-by-piece inspection, who knows the treatment that this particular window will require?

On that very subject, I was going to show you how we “diagnose” each window and how we make a simple but effective project plan which doubles as documentation for the client and saves a huge amount of time and money.

But this letter is already long enough — I hate detaining you from acting in the world.

Until the next time therefore, about a fortnight hence, unless you have a question, in which case you can write a comment, and we’ll reply.

I'm fascinated by the whole subject of "restoration" in glass. Several years ago I had to make new pieces to replace missing glass in the border of a window. Luckily they were a simple zigzag-and-stippling pattern. I very strongly believe that any such work should be invisible from normal viewing distance but detectable as non-original under magnification, so instead of stippling I did "spottling" as you refer to it in your instructional videos. The result was perfect without running the risk of anyone in future confusing the original pieces with my replacements. Carrying that one step further, I completely understand your position on the ugly dogs. I was reminded, though, of something I'd read in Ballantine's classic "Treatise on Stained Glass" where he said: "Never imitate such figures as No. 1. on Plate VI., or No. 1. on Plate VII., even although they may be genuine antiques. Should the costume belong to the period you have to illustrate, adopt it, but improve the drawing and proportions of the figure, and this will sufficiently represent the period, while, as a work of art, your design will be free from deformity. No. 2. on Plate VI., and No. 2. on Plate VII., give an idea of the change which can be effected by such treatment." The first of those two pieces showed a knight in armor that had awkward proportions and primitive execution, but that was original and contemporary with all of the rest of the window. The second showed something that looked refined and elegant and thoroughly modern in execution, utterly unlike the original. Had the first figure been a crude repair like the twin dogs in your example, the replacement would have been fine with me. But replacing a true original with something that's prettier is just wrong in my mind. I wonder how much of this sort of vandalism has gone on in the past, and how much of what we admire now might really be later "improvements on originals" made by followers of Ballantine's principles?

I would like to think with you on this issue of repainting. This was also a question that I had to analyze during a restoration.

It seems to me that the technique, how the pigments are mixed with a solvent and applied to glass and fixed with heat, has not changed much since Theophilus' manuscript in the 13th century.

So, during the restoration, if there is a glass fragment that has lost part of the design or it is light, would it be a problem to repaint or strengthen the design, following the same lines that the artist used? And why not fix this intervention in the kiln? If the intention is to retain the characteristics of ancient techniques, what is older than Theophilus' technical descriptions of glass and stained glass? Indeed, if the glass fragment with failure or loss of design undergoes a restoration reversal process, what is the chance of it getting worse?

I would like to discuss this theme present in our work. I do not intend to create controversy with the subject.