I have always sought to pull back the curtain on our studio and thereby disclose the whatever-it-is that works for us.

This could mean telling you the specific tools and brushes that we use.

It could mean spending a seemingly bizarre amount of time on some hitherto uncelebrated topic such as how to mix your glass paint.

Or it could mean breaking down a technique to reveal the distinct steps which will otherwise rush past you in a blur when that technique is performed at its customary speed.

Today, it’s a little of all three. But I must be clear with you: despite my thrice-repeated promise to teach “the undercoat” the very next time I wrote, I have resolved to break my promise to you once again.

You see, there is another preparatory task I judge we must explore. I hope it is the last one. However, if I should identify another, I will stand fast again, because not to do so could be more misleading than if I were to publish a beautiful but boastful video which, while it enchanted you — and who, these cacophonous days, does not sometimes seek enchantment? — left you none the wiser: I would rather risk that you are disappointed or displeased with me than that I should fail to give you a small piece of information which has the potential to cause a revelation.

If you don’t know about the task you are about to witness, I solemnly attest to its importance.

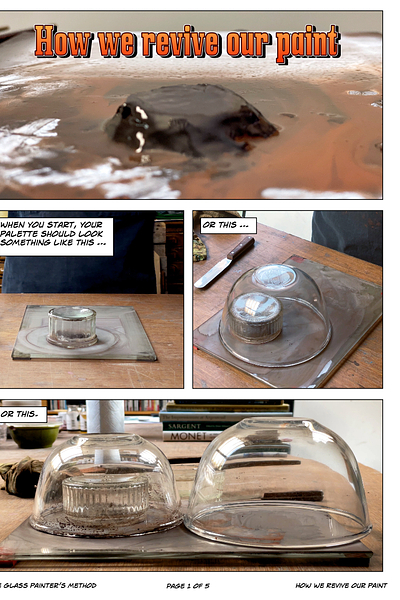

It is what we do each morning and then often less elaborately, though always as required, throughout the working day: we revive our paint.

“You revive your paint? — this dull topic is why you break your promise to us?”

Yes. I understand the topic might seem small and trivial. But remember this: I am the antithesis of the flamboyant stage magician who must withhold his secrets because he knows disclosure would break his audience’s bewitchment.

If you do as we do here, you will attain a relationship with your paint which will permit you to achieve all kinds of wonders with it.

Furthermore, you will remain bewitched, albeit with your own magic, as opposed to ours. What happier outcome could there be?

Here are the kinds of tactics we employ in order to revive our paint and so prepare it for whatever challenges the working day might cast its way.

Newcomers, please note: this is how you “turn the key and start the engine” of successful glass painting. It is not a 3-second operation. It calls for time and focus. No sooner do you give the process the consideration it deserves than rich rewards will start to flow your way.

I hope the video has been worth the cost to my battered reputation.

By all means download this overview to contemplate the process in a different way:

I must leave you now.

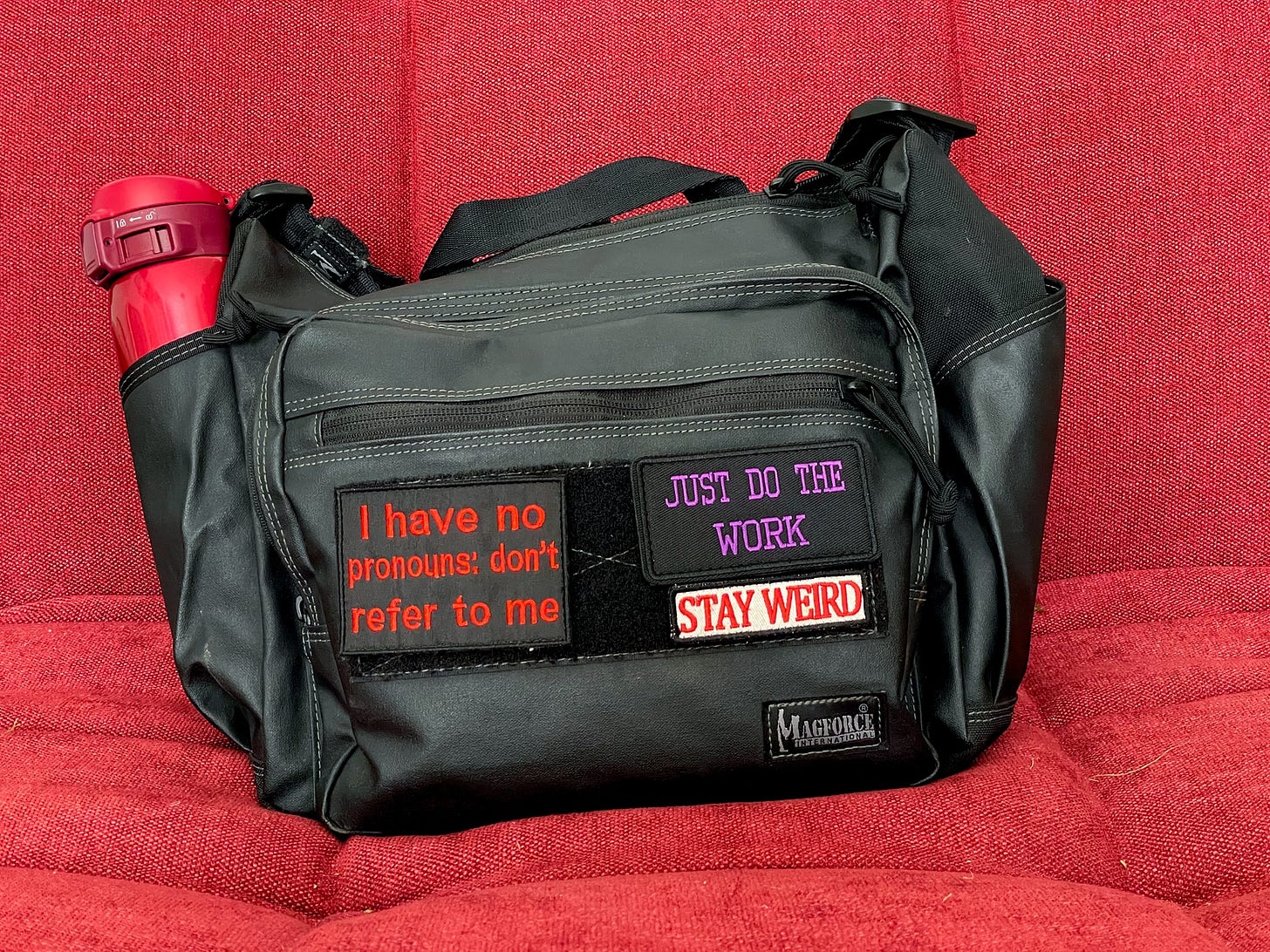

PS further to my last letter, some readers privately expressed a kind but thoroughly misplaced bewilderment at the suggestion that I might be difficult to work with. I therefore submit as further evidence, which I consider dispositive, a photograph of my studio workbag:

I imagine there’s something here to offend anyone should he be that way inclined.

PPS by way of preparation for that momentous and long-awaited time when I shall initiate our dive into the undercoat, you could do little better than dwell upon these three sentences I have extracted for you from one of the few great books on stained glass:

“Do a face on white glass in strong outline only: step back, and the face goes to nothing; strengthen the outline till the forms are quite monstrous — the outline of the nose as broad as the bridge of it — still, at a given distance, it goes to nothing; the expression varies every step back you take. But now, take a matting brush, with a film so thin that it is hardly more than dirty water; put it on the back of the glass (so as not to wash up your outline); badger it flat, so as just to dim the glass less than "ground glass" is dimmed; — and you will find your outline looks almost the same at each distance. It is the pure light that plays tricks, and it will play them through a pinhole.”

Stained Glass Work by C.W. Whall, Chapter VI (London: John Hogg of Paternoster Row, 1905)

“Hardly more than dirty water” — small and trivial, anyone? — yet the undercoat is wonderful all the same, as you will see.

Until the next time. (I now know better than to make a promise about the content.)

3 comments. First, I remain in awe of your writing talents. Second, it literally never occurred to me that the wash could go on the back of the piece as per the Whall quotation. And third, going way back to the first video (I think) I ever saw of yours, the one regarding the importance of the "lump" of paint, I remember being fascinated by how dry and unpromising it looked when first mixed but how it had magically turned into a very workable gell after simply sitting overnight. I have to confess that I haven't been successful in duplicating that yet but I wonder if there's some sort of slaking process going on, whereby what looks like a dry(ish) mound actually is trapping little globules of water that gradually soak into the pigment and binder particles over a period of hours. That might explain why I often ruin things by getting impatient and sloshing in more water until things start flowing, only to find that there's actually too much water to do any clean painting. Much to learn here!

If anyone had told me about 10 years ago, before I first ‘met’ you both, that I would find watching a person mixing paint so absolutely fascinating and absorbing, I would have laughed him all the way to the nearest asylum. Since then I have watched you mix and revive paint in the videos so many times that I’ve lost count and it’s still fascinating and absorbing. And it works. Now I’ve just watched a whole week of you mixing paint and it remains amazingly hypnotic. I guess it’s a glass painter thing ;-).

On your other comment Stephen, I can’t imagine you being difficult to work with. Exacting, precise, focused, picky and a perfectionist maybe, but not difficult.