In these letters, while my mind remains clear, I propose to talk with you — and with my daughter who left home six months ago to practice drawing — about two topics.

First, the key techniques of traditional, kiln-fired stained glass painting.

Second, a restoration we began and finished whilst under lockdown.

I’ll begin with the second topic — the restoration.

This will give time for anyone who wants to “paint along” to buy the brushes, paints and tools (we don’t take commission from suppliers); and to learn how mix the glass paint, which no one will deny is quite a challenge — that’s why this guide is worth a student’s time.

The restoration: I spent an obnoxious half-hour debating with myself whether to start big and show you around the whole building first; or whether to start small and jump straight in with the wreck which one particular window had become in the 160 or so years since a collection of immeasurably talented Victorian craftsmen first designed, cut, painted, assembled and installed it.

Calming myself, I resolved to jump straight in with the wreck.

That way, I reasoned, those people who don’t give a tinker’s curse for architecture and historical context — spoiler: one day soon I’ll show you the original invoice for the whole window (less than two hors d'oeuvres in a Hollywood restaurant) — can leave (quietly, please) and get on with whatever-it-is that satisfies their barren souls.

Fair warning: I’ve no interest in becoming a YouTuber, an Influencer, or someone with his baseball cap on backwards who shouts “Hey, what’s up, guys!” whilst lifting his hands in the air then pointing down with both index fingers like a complete and utter jerk who doesn’t realise he’s a slave to the medium which he imagines he is master of.

On the contrary: video is my tool. I’m in charge here. It does what I say. And what I say is, “No fancy bells and whistles”. The point is always to get off our backsides and out into the world and do things — hopefully, good things, although it’s not often given to us to know for sure: hence why mankind’s world-be utopian improvers should usually and more usefully shove off.

Thus, in order to get on with showing you the long process of repair, here now is the wreck, in bald, plain words—the wreck as it was before we started work on it:

Next, for a before-and-after comparison which you can inspect at your own pace.

Unfortunately, I photographed the original window on one light box and then, three years later, I photographed the restored window on a different light box.

It’s a different light entirely.

I have neither the skill nor the desire to compensate truthfully for the different wavelengths.

Hand on heart, the finished window looks beautiful. I’m just sorry for the imperfection here:

But I certainly know enough to adjust the heights in photographs. It is a measure of my honesty that I have not exercised that knowledge — the restored window is shorter than the original one.

The reason is, we had to eliminate a few millimetres from the bottom.

For the snoops and credentialed snitches who are always watching and rarely adding to the sum of human happiness: we achieved this in a reversible way.

If you ever want us to restore the window to its original size, just give the word and pay the money.

Now, go away, you snoops and snitches, go, trailing your initials like slime. You’re not wanted here.

The change in height was made necessary by the fixing method which we’ll talk about another time.

Now for some background.

I say it’s a window, but really it’s a “cut”, that is, a section of a stained glass window.

This particular window has two cuts. (Others in the set have four.)

The wreck we’re looking at, within this newly started set of letters, is the bottom one.

Here’s the whole window — as we say, the top and bottom cuts — in their fallen state:

Let’s pull back a little further.

Here’s a faked photograph where you can see all 18 full-sized windows belonging to this project, and, on the bottom row, the 9 stained glass tops:

Take a moment and find the cut you’ll see us working on in these letters - I promise you it’s there, though everything’s so failed, it proves hard to distinguish one wreck from another.

I say it’s a “faked” photograph because this is a bay window. Unless you stand close by, one column on both sides will stay hidden from your sight.

Here is too far away:

Here is closer:

You might wonder why there are only tops on the bottom row. I don’t believe for a minute it was for lack of money, but rather so that:

People can enjoy the view.

And not get confused, thinking they’re in church.

Between the wars, the room was used to serve teas in:

That was the nostalgic period evoked by Brideshead Revisited: “Great Gatsby” if you wish, though with class and taste, when even Catholics didn’t always think of church.

Now I wrote “bay” window but I’ve also seen it called an “oriel” window.

However, I’m not sure that’s right because the three top rows - this will be where the stained glass eventually goes - are supported underneath by a lower floor with two rows of windows giving onto a separate room:

Bay or oriel: I won’t press the point because the last thing I want is to engage in a pernickety debate with a psychopathic specialist in architectural nomenclature. Can we just agree it’s big? (US subscribers: I know, I know, it’s small.)

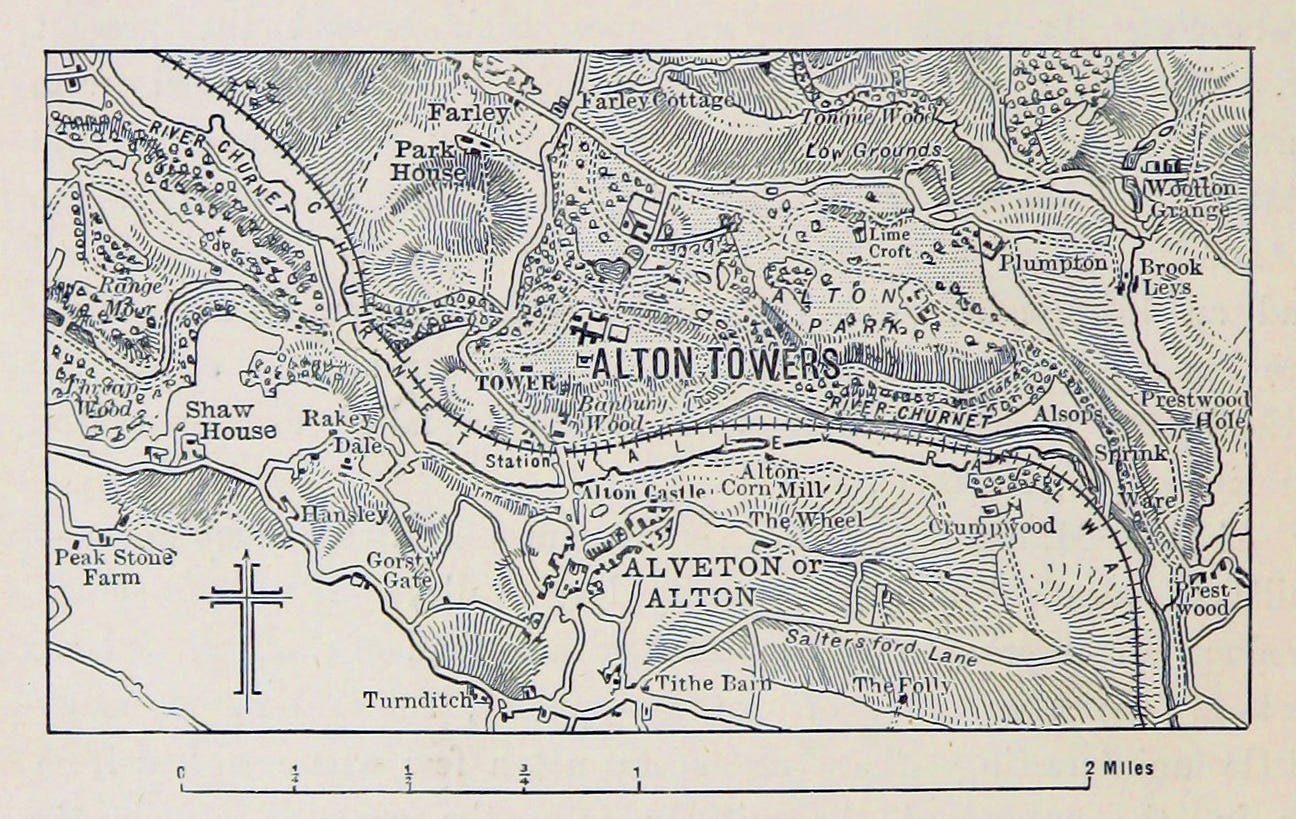

Stepping back so you can see the building called Alton Towers: here’s a nineteenth-century watercolour of the castle and those same grounds onto which the bottom row of windows looks (because as you now know there’s no stained glass to conceal the lovely view):

And, yes, here’s the bay window where the stained glass will go:

Next, not so much as stepping back as taking flight, here’s an old postcard which day-trippers could once buy and send from Alton Towers:

Upwards, again:

There’ll be lots more to say about history and context but that’s enough for now. I’ll leave you with a press interview which happened at the installation.

If you listen carefully, you’ll hear David convey the scope this project was: the size is so fresh in his mind that the labour is still painful to look back on, despite the joy which everyone will feel to see the window brought back to life:

Each window required considerable re-painting. Stretched end-to-end, I wonder how long these lines of paint would be.

Until next time, when we’ll take up our other topic, techniques, starting with the undercoat.

“Where else to start?” as I know that Nathaniel Somers would say.

Now we know why you both have been so busy!! Its wonderful to see you two again. Its also refreshing to see all the history behind this project and the building. It paints a full picture for the viewer and the student. As a restoration artisan myself, I always try to search into the history of the glass I am working on as well. I believe we are all leaving a legacy for others and its so important to respect all the materials and craftsman techniques. Thanks for all you do! You both are masters at your trade and the world is a better place for it!

how long did that particular project take?