I have been methodical:

How to mix your glass paint, here;

How to restore your glass paint each time you set yourself to work with it, here;

How to cut and prepare your glass for weeks of happy practice, here;

A fly-by of the key techniques, here;

What the first technique is — the undercoat — why it is the first, and how to practise it, here;

The second and third techniques — highlights and softened highlights — and how to practise them, here;

And then everything in this strand I have collected beneath the “Techniques” link on the menu, here:

(Likewise, my letters to you concerning restoration are assembled underneath the “Restoration” link. I like to assemble these letters together where they belong so that you can find them easily.)

Therefore, you cannot say I haven’t been methodical.

Whether, however, many members of the set of people I had it in my mind to write these letters for have paid me much attention — that I am inclined to doubt; not even my own daughter (although with teenagers I admit you rarely ever know).

Yes, I have been methodical, but my suspicion is I haven’t been effective …

People ask, “When’s the next class?”, then most of them seem comforted when the schedule does not work for them.

Indeed their mannerisms and words suggest that I now treat them with contumely because I wilfully construct a path before them in these letters which you (and you alone, not they) are reading: “I have to take a rain-check — too busy now to read them,” they splutter, hasty to maintain their upright shiny image of themselves yet catch those ‘thrilling’ episodes they missed on Netflix.

Had I but a penny for every time I’ve heard “I always wanted to learn to paint stained glass, I just never had the time”, Croesus would seem a foul and ragged beggar by my side.

But I am of such a wayward crooked disposition, I only relish speaking ill of people directly to their faces (and by hypothesis those folk are elsewhere watching Netflix).

Which is not to say I only relish speaking ill of people: you who read these letters, and you who practise the rehearsals I propose, are admirable to me.

Praise — deserved and hard-won praise — is ever my leading cause of pleasure.

It’s true: I love battling with contemporary inanities, standing my ground, pushing back, seeing the glint of panic in an adversary’s eye when it dawns on him that the rubbish he’s been spouting (thinking it would protect him and promote him and make him rich, because money salves his conscience and obliterates his reason, much like the Pardoner in Chaucer but without the self-awareness) is impotent.

“Ah, friend of mine, believe me, I march better

’Neath the cross-fire of glances inimical!” (Cyrano de Bergerac, Act 2, scene viii)

What intrusions will not some men permit to head and heart in order to win promotion and earn money? — I am fortunate indeed I left the City of London and whole world of Finance.

(Troubling questions which disturb my dreams by night: How would I have failed and fallen to corruption? How weak must my will be, just to have succeeded through absence of temptation? What “success” is that?)

That delight in confrontation on one side, it is as I confessed: my deepest pleasure is witnessing another soul’s real accomplishment which he or she achieves through patience, focus, hard work and indeed devotion — a seed that sprouts, grows, then flourishes and blooms — as happens when someone disciplines his mind and hands to learn a craft, any craft, in our case here, the craft of traditional stained glass painting.

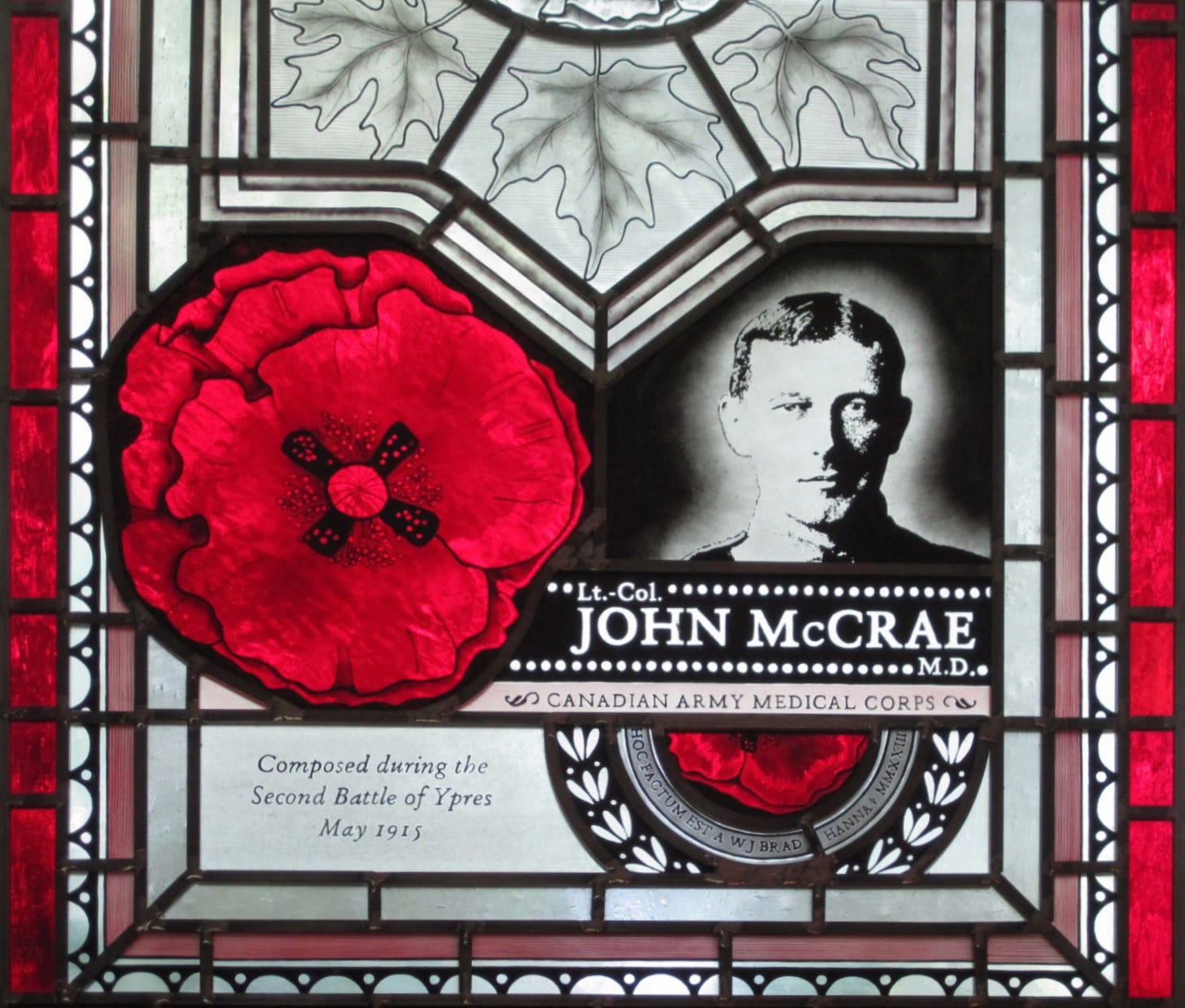

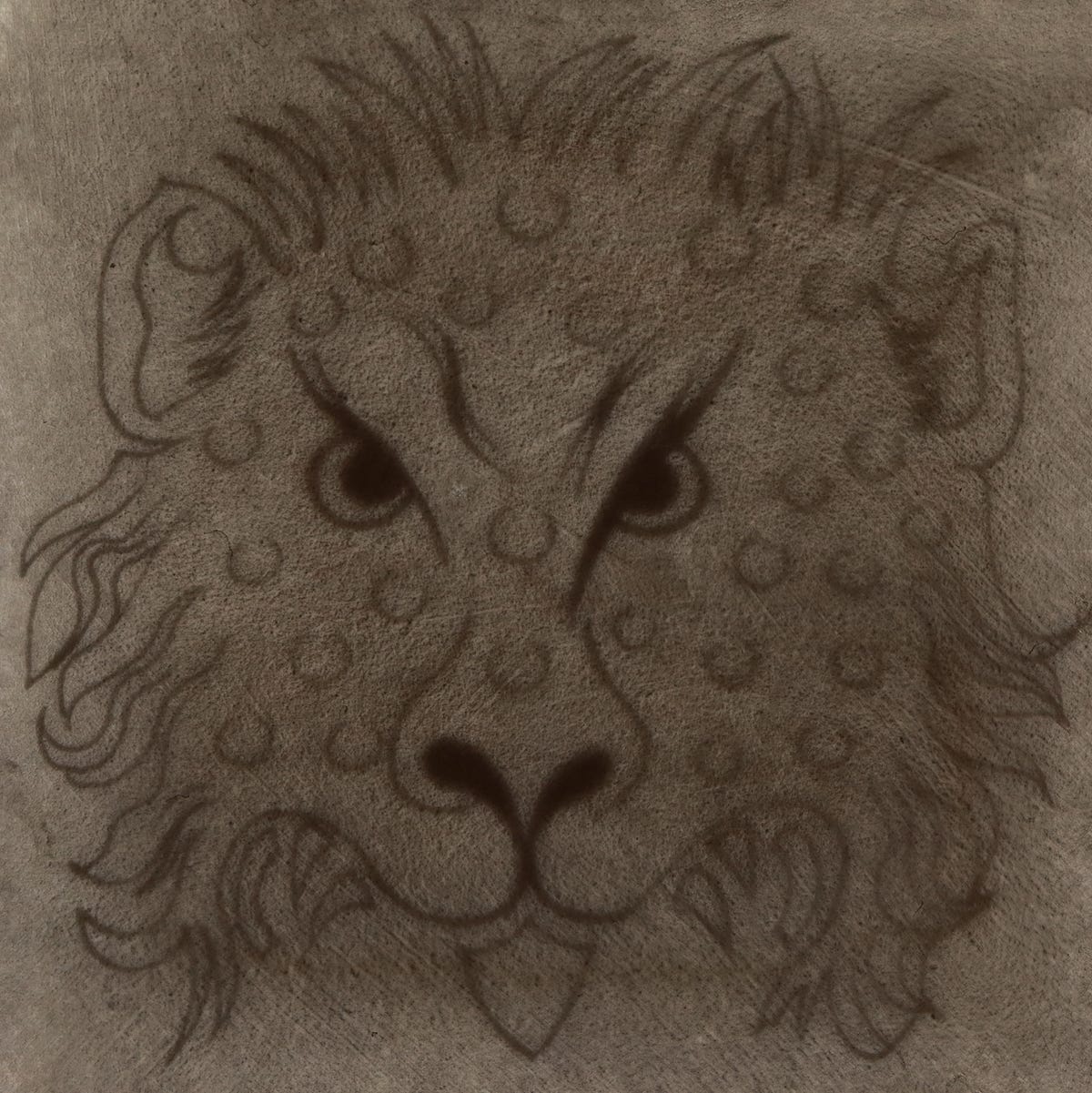

For instance:

And:

Other people’s triumphs — they furnish me with evidence I do not toil or suffer for my faith alone.

Let’s continue now because once more I crave my deepest pleasure, although it shall mean work for you few who strive and who therefore also grow.

Our newcomers start always with the undercoat (not with tracing) — what do they thereby learn?

How to mix and revive the paint and organise the palette;

How to hold the knife, the hake brush, and the badger blender;

How to clean the light box and the glass;

How to mix, load and apply good undercoating paint (which, later on, is also what they can use for certain kinds of shading);

How to use the blender to move paint around — to leave it smooth or to agitate it and leave behind a texture;

How and where to put down the tools and brushes so they can efficiently be retrieved the same moment they are needed.

Any teacher who starts you off with tracing is, intentionally or not, stacking the deck so that only students wearing life-jackets so to speak (and also mix-up metaphors) will float.

After an hour or several of frustrating but ultimately fruitful practice, once the newcomer begins to appreciate the pace — each technique has its own speed, which largely follows from the consistency of the necessary paint: flooding, for instance, must be swiftly executed or everything is lost, whereas tracing must at least be capable of near-glacial slowness — then highlights can be introduced like Circean fruit to distract the Odyssean glass painter from wandering further …

… though not to change him into pig or other beast: for how then could he hold a brush?

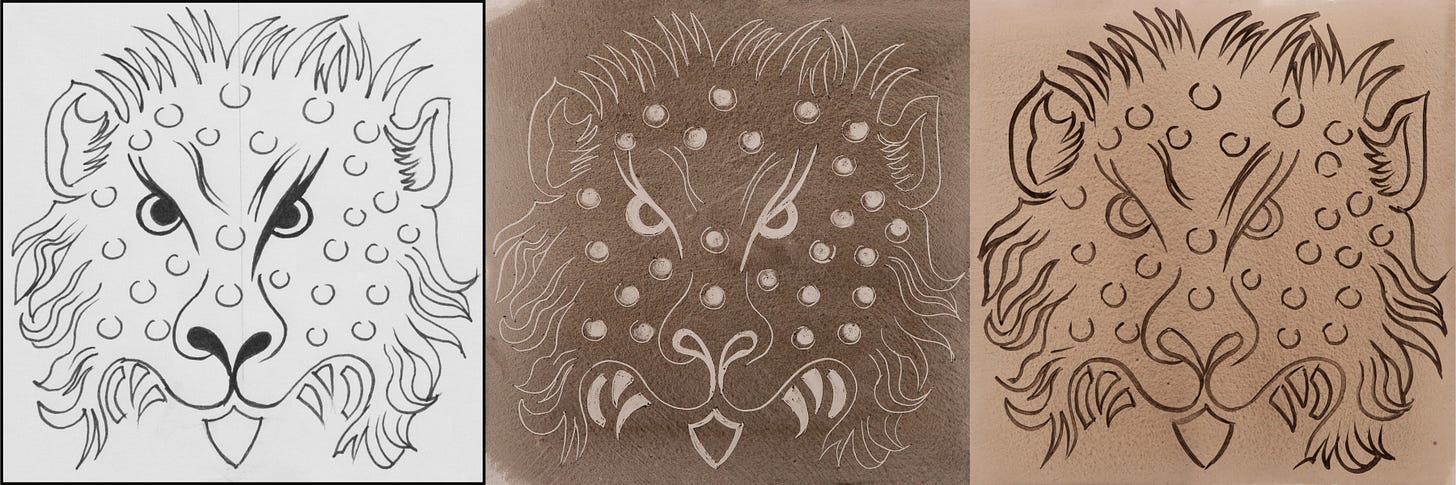

Concerning highlights, I never gave you the design for this beast, did I?

Which omission I now remedy, although, should you want an introduction to the technique of cutting highlights, first go here to Letter 5.

When he’s ready, this design will long distract the newcomer:

Here’s the bald sequence, for that is all you need now, starting with a lovely tint of yellow glass:

A dark undercoat …

… but not so dark you cannot see the design beneath

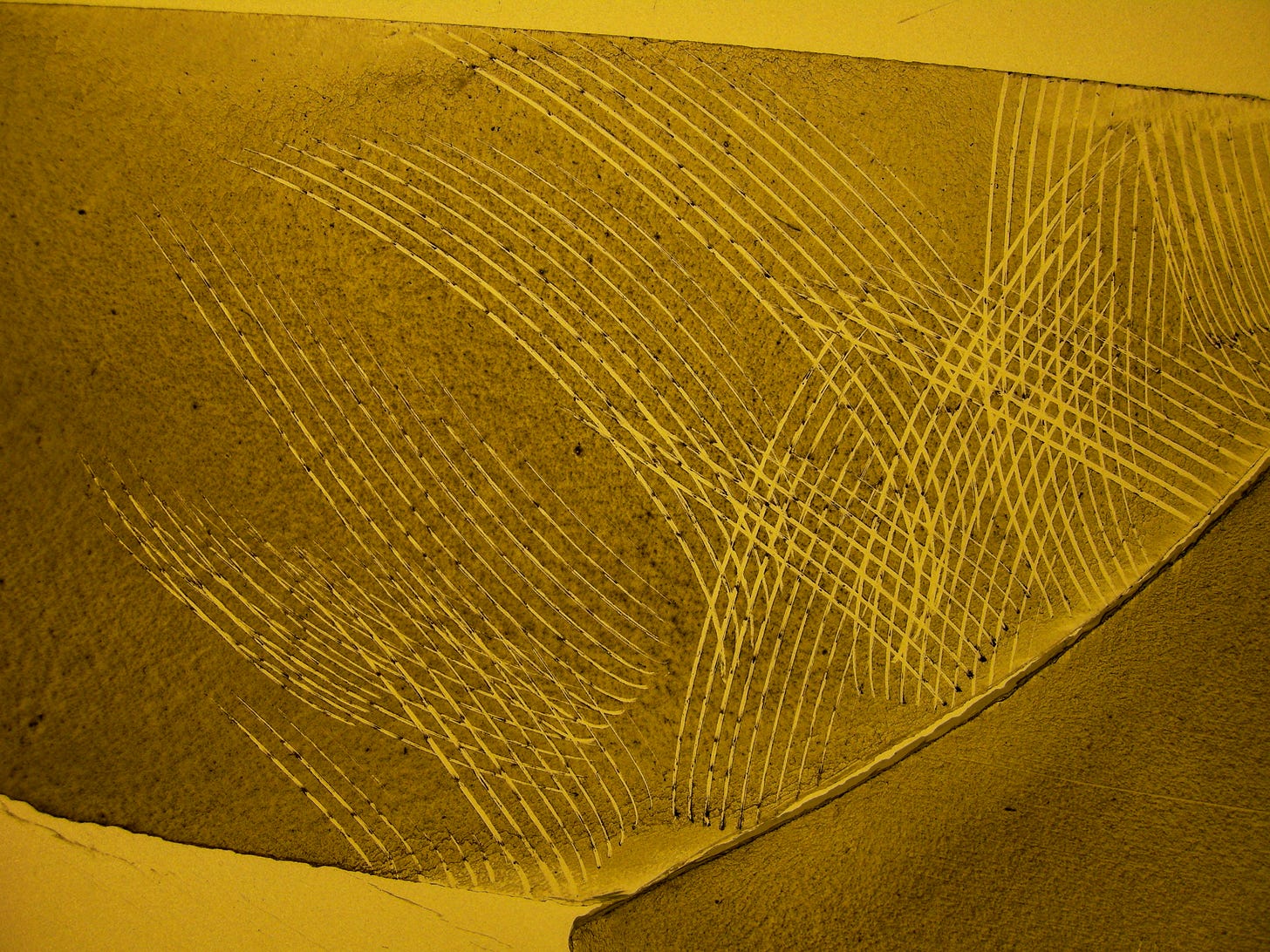

Use a thin and pointed stick to cut the lines:

Which brings you here:

Use a more substantial stick to cut the more substantial highlights:

Which brings you here:

Finally, give the leopard the spots he has been calling out for:

Thus:

This is an example of where an adept teacher might lead a newcomer with but a few hours’ practise.

Or, working with these letters, my hope is that the newcomer can even make his or her way there alone, and thereby reach closer to the palace of their dreams.

I also want to give you information now for you to think about and then to put aside for later, when the question really starts to gnaw and bite. (Not that I wish anxiety on anyone. It’s simply that a lot of information is just noise until the moment comes when a person understands how much he needs it.)

In this early period where he is now, the newcomer is cutting highlights in the places where, later, he will paint trace-lines:

That’s all clear: the design displays the trace-lines which for now, while he is learning, the newcomer employs to cut his highlights:

So where, when that time comes, does the glass painter cut the “real” highlights?

Where indeed?

For us, because we are decorative as opposed to truthful glass painters, our answer is: the glass painter puts the highlights wherever they look most beautiful.

“And where is that, pray?”

Whilst only experience will provide the answer and therefore by its very nature must sometimes lead each one of us astray, here’s what the newcomer can meanwhile do to soothe anxiety and inch his own way forward:

Thus:

If the highlights don’t look good to you on paper, you have likely found a clue they won’t look good on painted glass. On paper, though, you can rub them out and try again. Not seeking to cause panic amongst the uninitiated — I report the honest truth and hope I do not suffer for it like Cassandra: on glass, if the marks look bad and you proceed regardless, the odds are you are stuffed.

Start wondering already “Where will I cut my real highlights?” and your mind will find all kinds of answers when time comes for you to meet this challenge.

Thus we use highlights to distract the newcomer so that he lingers with the undercoat (which also means he experiences working from a bridge, starts learning how to keep it stable, and more than likely gets a useful lesson about the bad things which happen when he touches unfired painted glass): highlights are the first distraction.

The second distraction is to outline the journey so that the newcomer knows that he or she is on their merry way, which knowledge can relieve impatience. The journey goes like this:

Undercoat

Highlights

Softened highlights

Flooding

Tracing

Strengthening and

Emboldening

Do you detect the pattern?

Light (stages 1-3)

To dark (stage 4)

To light again (5)

And back to dark (6 and 7).

This sequence means there is always a helpful contrast between the density of paint the newcomer is learning now by comparison with the density of paint belonging to the previous technique he practised.

He swings between extremes, which, though it can seem manic, helps to keep things compartmentalised where they belong for now.

There’s a further piece of information I wish to lay before you at this time, because not to do so risks entrenching a false surmise: the order in which the newcomer learns and becomes confident in the key techniques is not the order in which the key techniques are likely ever used.

There’s no harm in that, is there? — learning things out of sequence?

But it likely points to why most teachers plain get it wrong if their hope is that everyone (not just the innately talented) should triumph through hard work. They start instead with — you guessed it: tracing. Which, as I would have it, is the numbskull’s choice of starting-point. Better by far to start the newcomer with a broad stroke …

… than to confront him with the demand that he produce a slim and elegant line:

No glass painter can achieve anything unless he first understands the character of his paint, which takes some time.

Therefore we don’t trouble the newcomer with the tracing brush till later (though later he will mainly use it before he cuts his highlights, unlike the sequence we are following right now which was my point precisely).

Now those of you who’re learning as you read these letters, you have the leopard you can practise on until we start with flooding next time I discuss the key techniques with you.

And also these designs which I now gift to you - a king’s head:

And a lion’s:

They are wonderful for practising the undercoat and how to highlight.

Looking far ahead, however, I judge it will help you to see highlighting as you will do it when you’ve accumulated a few more skills. It helps to see ahead, I always feel: to know where you are going and what will then be asked of you.

Here you are then, in a moment you will see a demonstration of cutting highlights and then softening them.

And the sequence which will bring you to this point is bare glass:

An undercoat:

A bold trace:

A wash and blend:

Flooding:

Some strengthening and details:

And now to cut the highlights as well as soften them:

Thus:

Therefore of the seven key techniques, we’ve now broached three. About those three, I’ll have far more to say but next time we’ll start flooding, the darkest paint of all.

Trusting that is enough for now, I’ll bid you farewell then I’ll retire to my sanctuary where I will pray for your success and therewith my delight.

Farewell.

And please pass this letter on if you know someone who wants to learn the craft:

Mea culpa, I suppose. I read your letters and watch your videos with great interest, but have I picked up a brush and done any actual painting? Sadly, no. I've been bedeviled my entire adult life with tremors in my hands. My doctor has thoroughly checked it out and says it's a genetic thing. My few remaining immediate family members have the tremors as well. When I discovered glass painting half a dozen years ago, after retiring from decades as an office worker, I was excited and fascinated by the whole thing. But I quickly found that the tremors that had kept me from painting tiny details on model airplanes as a boy, or from making smooth beautiful soldered seams on stained glass panels were blocking my ability to make the sort of clean, sweeping lines that I saw in the examples in your book and class materials. Despite extended periods of struggle, the best I could do were lines that looked stiff and mechanical. I found that for a very limited range of subjects, that was OK. I can do very passable copies of old aviation and auto related advertising, for example. But the heraldic and figural subjects that form the core of "real" glass painting are virtually beyond my physical capabilities. On the rare occasions when I achieve something I'm happy with, it's only after hours and hours of struggle and disappointment. Then there's the question of what to do with all the accumulating pile of fired pieces. There doesn't seem to be any demand locally for such things, and there's only so much glass that can fit in a person's own home. So I suppose I'm in the category of people who sign up for your material without really using it, but it's because I am sincerely fascinated by the processes and tools and techniques in their own right. I may never be an artist myself but I love understanding as much as I can about how the true artists achieve their results.

I print all the letters, take notes, & highlight notable items and download all the videos. I have cut 17 individual pieces of glass to practice the images at the end of your book “The Glass Painters Method” and I’m now at the stage of tracing each image, to familiarise myself with the curves and lines. Once I feel proficient I’ll move on with my work.

While I’ve been busy hunting out and cutting glass, I’ve been practicing mixing my paint and stains😊It’s so relaxing especially if I have music on in the background. I also play around with mark making another relaxing activity.

My Daughter has become extremely wise over the years and has pointed out to me on more than one occasion, if you really want to achieve something, nothing will/should impede your progress and ability in reaching your goal. My only impediment is “me”