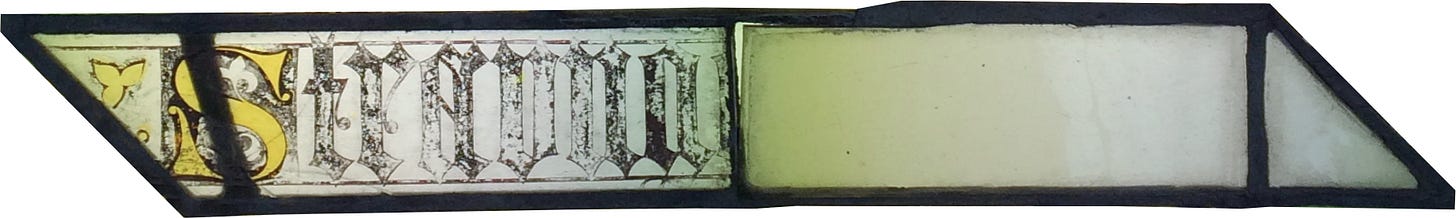

Should newcomers wish to review the earlier letters in this series concerning restoration, please go here and not anticipate I might repeat myself except when old age and madness make a fool of me — there is too much else that we must talk about. For example, moving brusquely on, today I write to you regarding the inscription. You will find it at the bottom of that one window (to be precise: the single cut) which, for the purpose of this present series, we nominated to signify the repair and resurrection of them all:

What’s that you say? The inscription is too small for you to read? Indeed it is, indeed it is. Its words — they are a mystery. Yes, a mystery, I say — and so do you. But, if you are agreeable, we’ll make a start, and find out where that takes us.

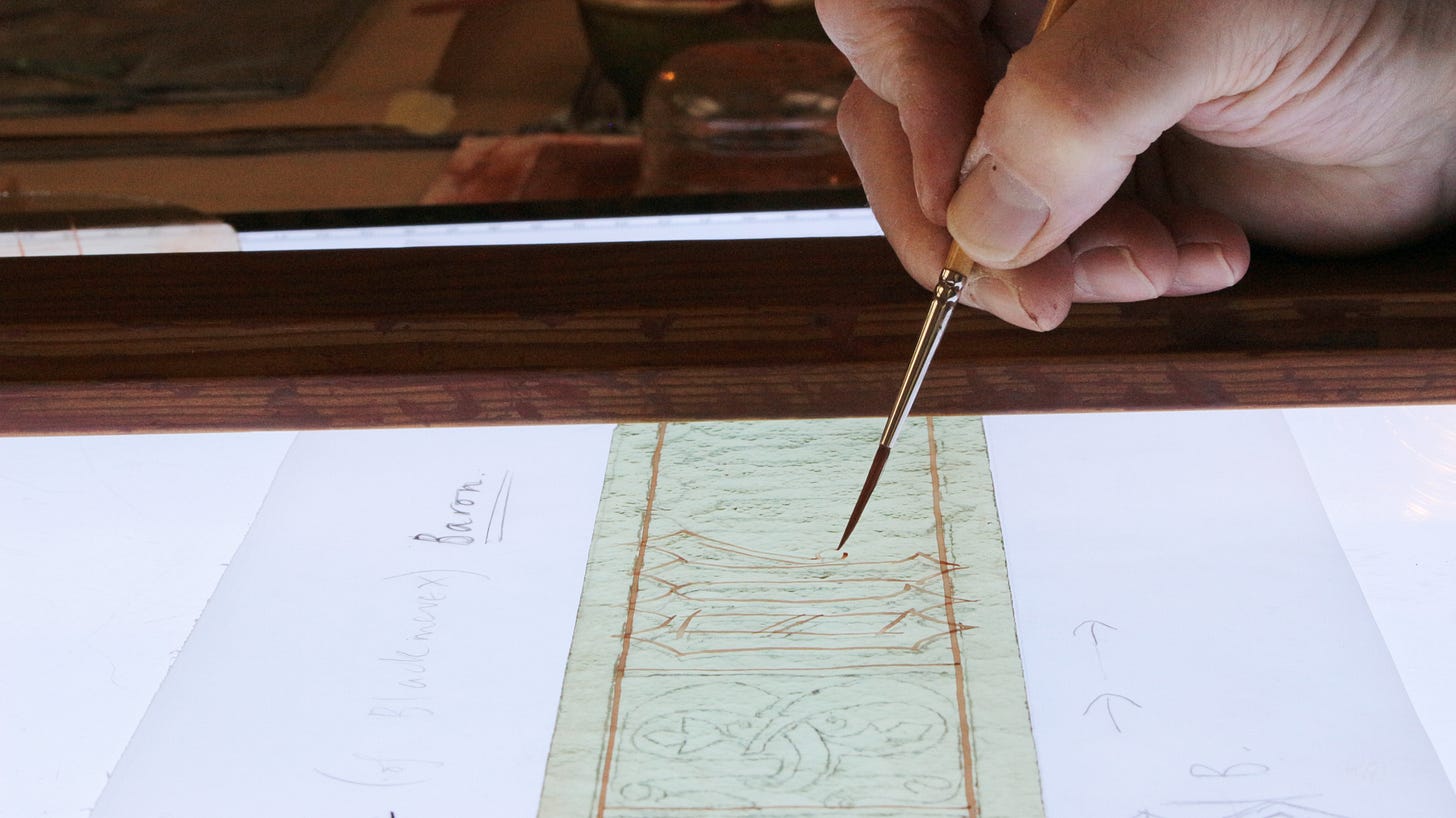

After you have revived your paint and cleaned your glass, the first step is to lay down lines, top and bottom, and trace the letters with as precise and dry a line as you can manage. Yes, glass paint can be dry and still flow perfectly, as I will show you in a later letter.

But now don’t charge me with hypocrisy because I elsewhere rave about the undercoat but omit to paint one here: I nowhere claimed all glass painting inevitably commences with the undercoat.

No, mine was the wholly reasonable suggestion that any newcomer whose first lesson consists in tracing (tracing!) can by that same token be absolutely certain that his teacher is a numbskull (see for instance my letter to you dated August 12th) — a different point entirely, which I still stand by, never caring that my conviction wins me no friends.

In any case, we have in hand a scheme to leave behind such faint evidence of tone as still remains:

It just so happens that, in this case, the tone will go down last.

Techniques, you see, are like that: whilst they have a standard order, the glass painter is sometimes obliged to juggle them around.

Be patient just a moment, for all will be revealed.

But, you ask, what is that word whose fragments yet endure? — and also, How did we identify the word whose painting is the topic of the present letter?

These are fine questions, both. Naturally, the first source we hoped would answer them was the full-sized designs themselves but, alas, we could not find them where they had been claimed to be — just this water-colour sketch which Pugin had asked J. H. Powell to undertake:

The sketch is charming: how well we can imagine it would delight the client. But its inscriptions are illegible — not to draw attention to the shields which are mostly fanciful.

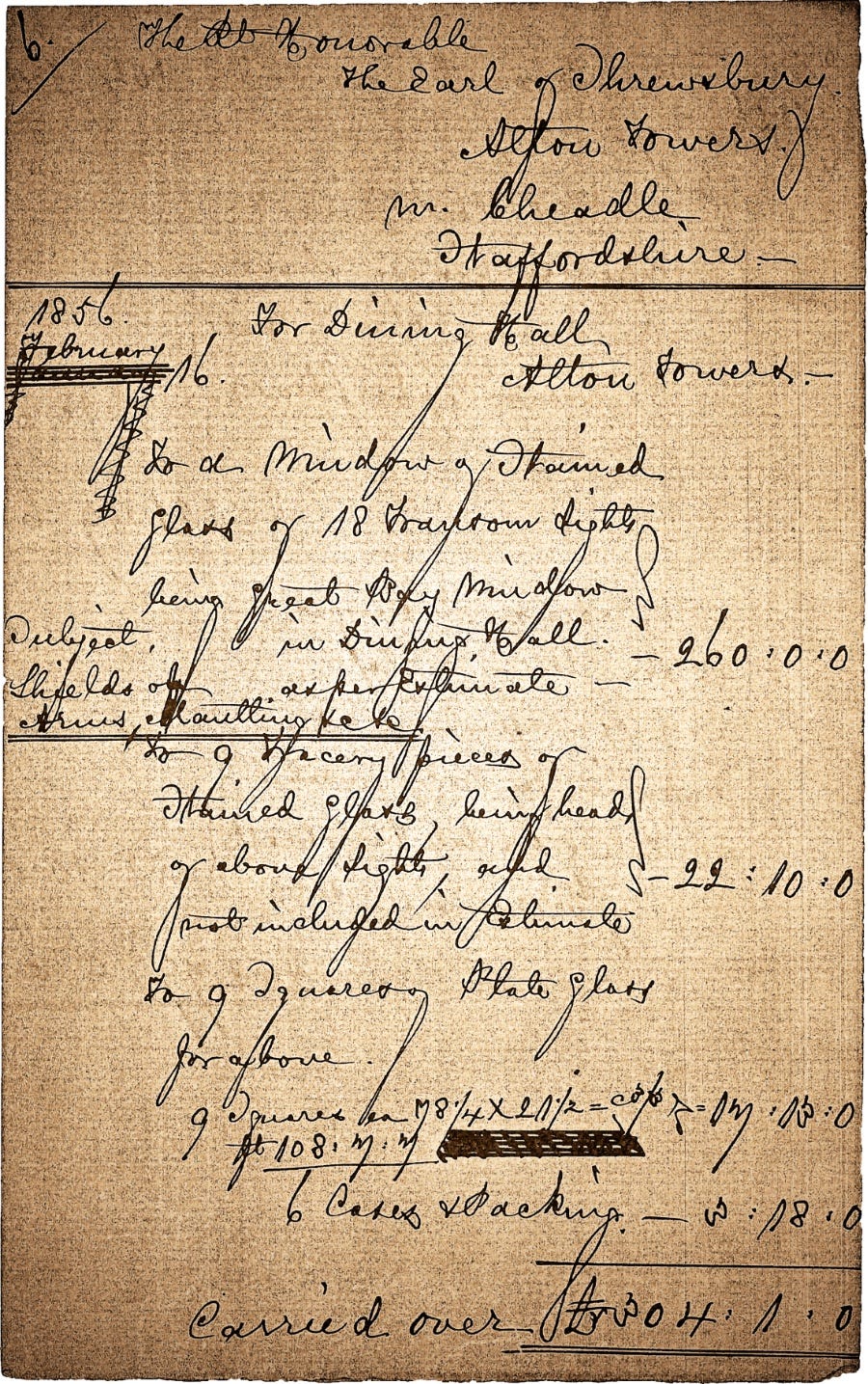

With considerable emotion, we also found the bill from February 1856:

Sadly, however, it does not list the individual windows. It only says — which makes me wince that governments and banks provoke inflation to tax and profit from us slyly —:

£260 for the 18 stained glass windows (stage whisper: Just think on that!)

£22 and 10 shillings for the 9 stained glass tops

£17 and 3 shillings for the clear glass beneath the tops

and £3 and 18 shillings for all the packing.

No help there then either.

Growing more anxious by the day, we scoured the internet and discovered many early photographs of that dark high-ceilinged hall, such as this one here from 1925:

But the inscriptions always proved illegible.

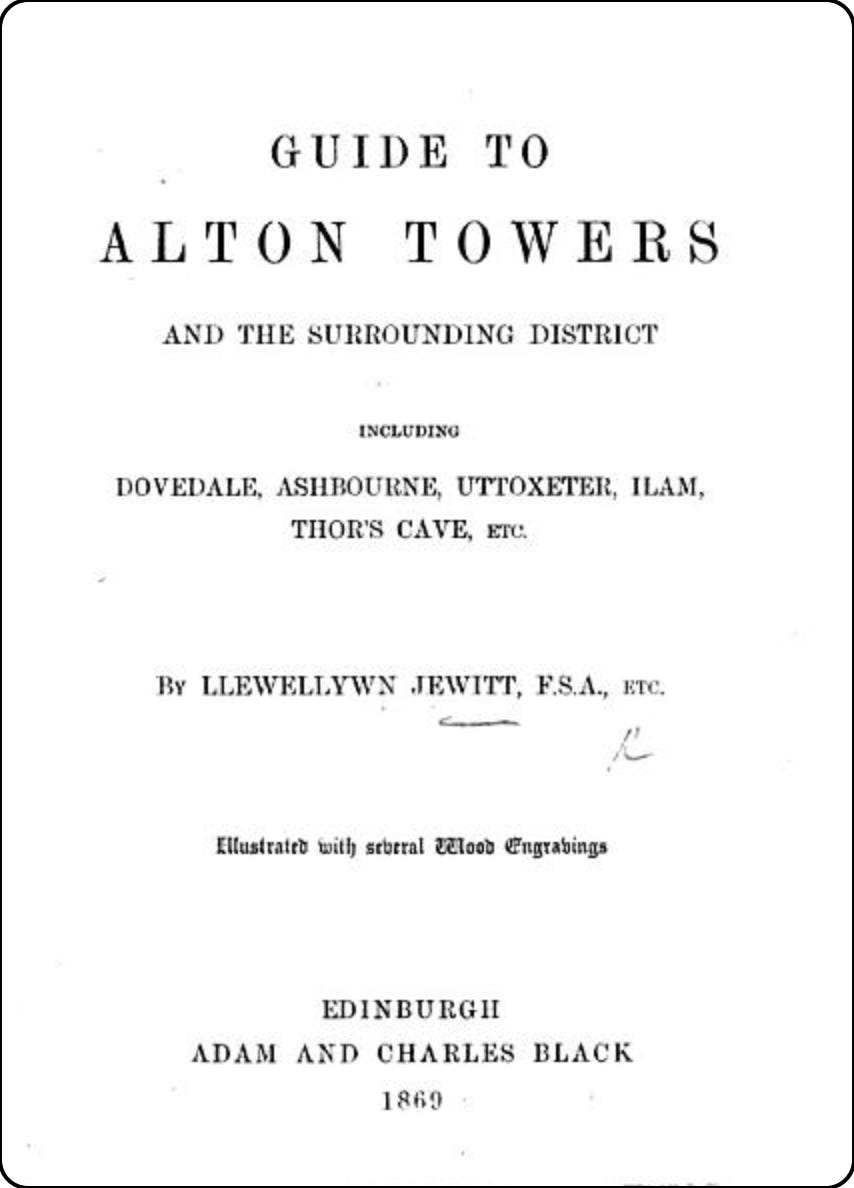

Then we found a near-contemporary book:

It informed us that the windows had been commissioned to trace the lineage of the Earls of Shrewsbury back to the Norman Conquest of 1066, and to celebrate the earls’ dynastic connections.

It’s quite a roll-call — you can almost hear the herald’s bugle:

“Talbot Earl of Shrewsbury, Clifford, Beauchamp, De Valence, Comyn, Mountchesney, Nevill, Middleham, Clifford, Bohun, Strange of Blackmere, Tailebot, Troutbecke, Claveringe, Buckley, Pembroke, Borghese, Doria, Lovetoft, Mareschal, Strongbow, King David, Raby, Lacy, de Verdun, Castile & Leon, d'Angouleme, William I, Bagot, Mexley, Aylmer & others”, the author of the guide book declares.

Seeking more information about the earls of Shrewsbury, we next made time to consult Burke’s General and Heraldic Dictionary of England, Ireland and Scotland (here), from which we soon established that John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, was also titled 10th Baron Strange of Blackmere:

With hindsight this next step might seem like grasping at straws: the name “Blackmere” was listed in Burke’s Peerage and in the guidebook as well as in the illustration which you see above. Whatever an impatient man might think, I tell you that inspecting every straw is precisely what the restorer often finds himself obliged to do that he might eventually be permitted to pursue his craft. In this devoted manner, when we researched the arms of Baron Strange of Blackmere, our excitement mounted when we came across this shield:

The reason for our thrill: it matched the arms belonging to the inscription whose painting process I will soon return to (the lower of whose two lions you saw painted last time I wrote to you about this project):

It’s not a perfect match. The stained glass counterparts, though definitely male, are not endowed. But I am informed this does not carry weight in heraldry: the attribution is not thereby undermined.

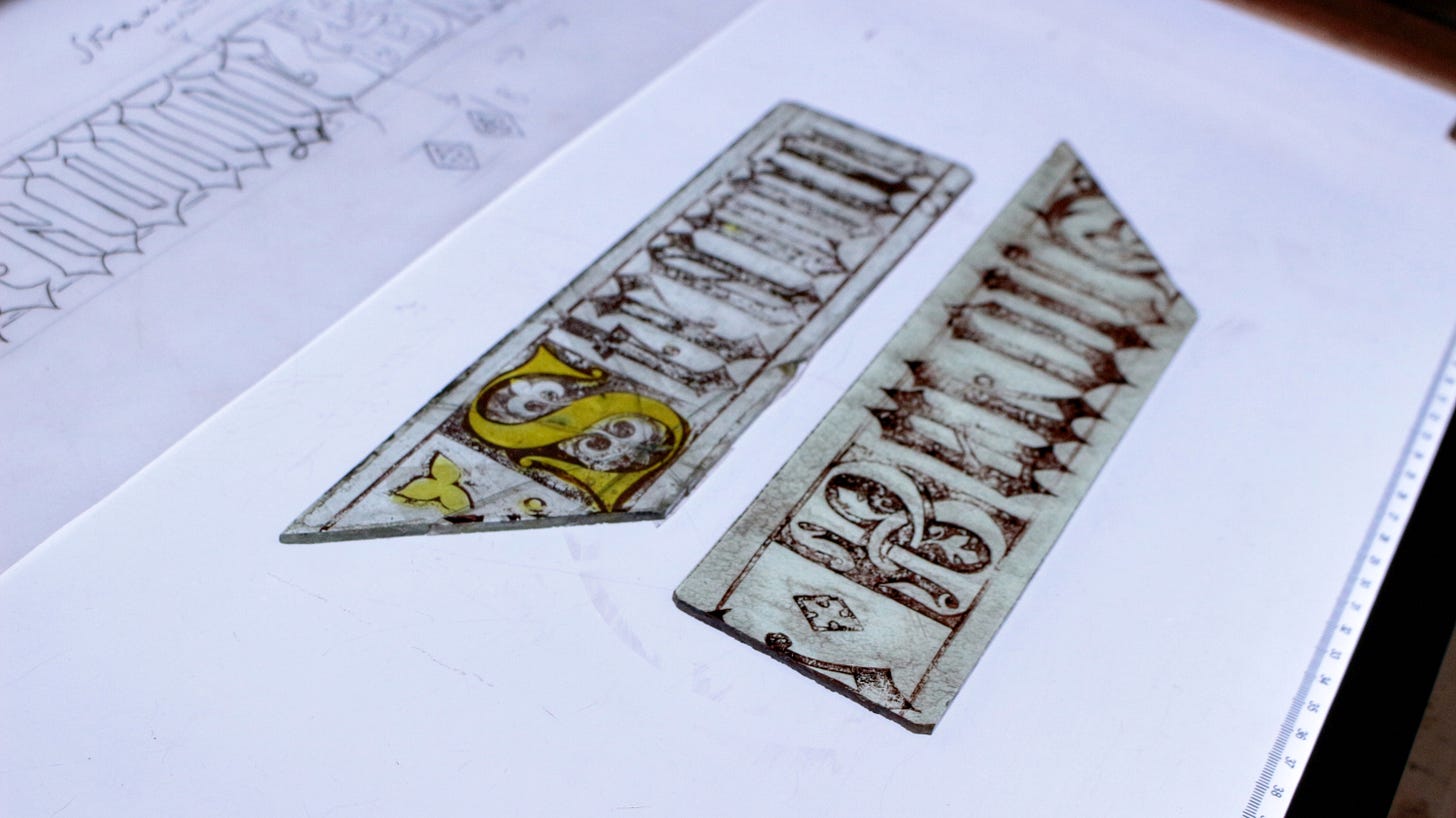

Therefore we confidently identified the letters on the existing ancient fragments as S … t … r … a … u … n … g —

And, although the last letter is cut through by a piece of lead, we speculated it was the beginning of an e.

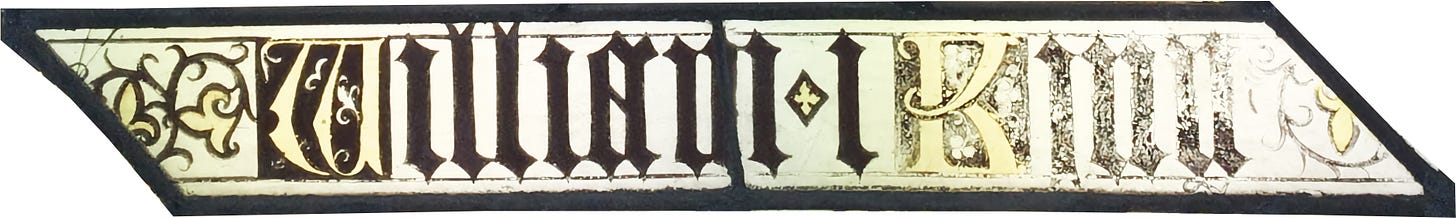

Our view that the last complete letter is a “g” might seem far-fetched, but we corroborated it by consulting inscriptions elsewhere in the window — for instance this one here:

“Engolesme”, a reading that is backed up by the guidebook we consulted earlier which cited “d'Angouleme” as dynastically related to Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury.

What then is the missing word?

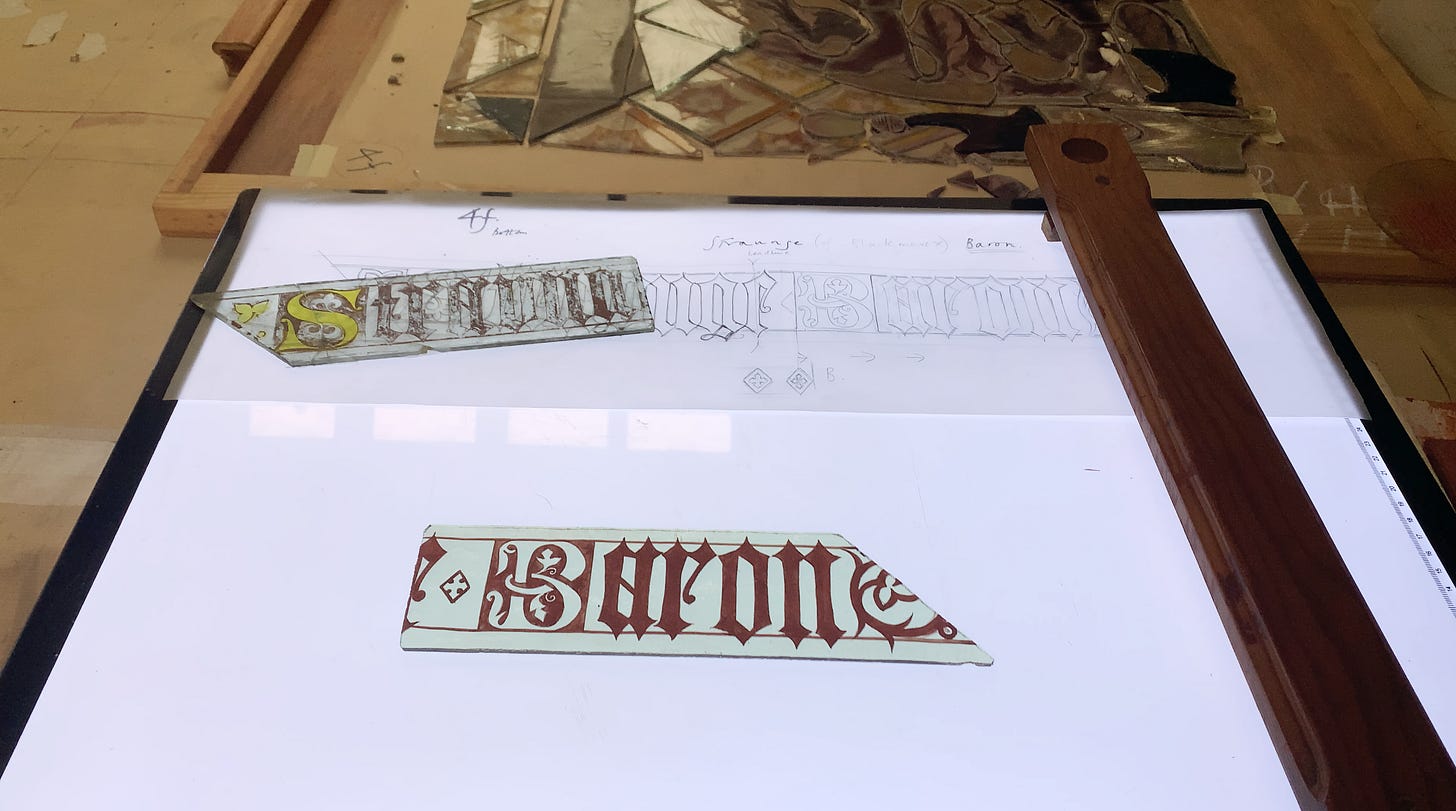

It will shock the truly academic to learn that we not only settled on “Baron” but painted it as well. The evidence we can adduce is that “Baron” is the established title, and that, elsewhere in the window, wherever the inscription includes a title, the name comes first, thus:

… for William the 1st, also known as William the Conqueror. (And see, another letter g to match the one in “Straunge”.) This reasoning is not water-tight — nor shall I strengthen the case against us by observing that the letters nicely fitted: a pathetic defence is ever there was one — but we chose to take a stand rather than leave the new glass blank.

I’m aware that some innocent reader might disparage this mad brew of intricacy and speculation. But restoration, in the same measure that it is historical, is also tentative: once evidence is lost, confidence becomes elusive. I promise you, I’ve cut a long story extremely short and spared you much detail from our long months spent hunting down a variety of missing words when all we wished to do was paint. There are whole tribes of glass painters who appear to get a throb from paper-work: though I once long laboured in the Bodleian …

… their party is most definitely not mine.

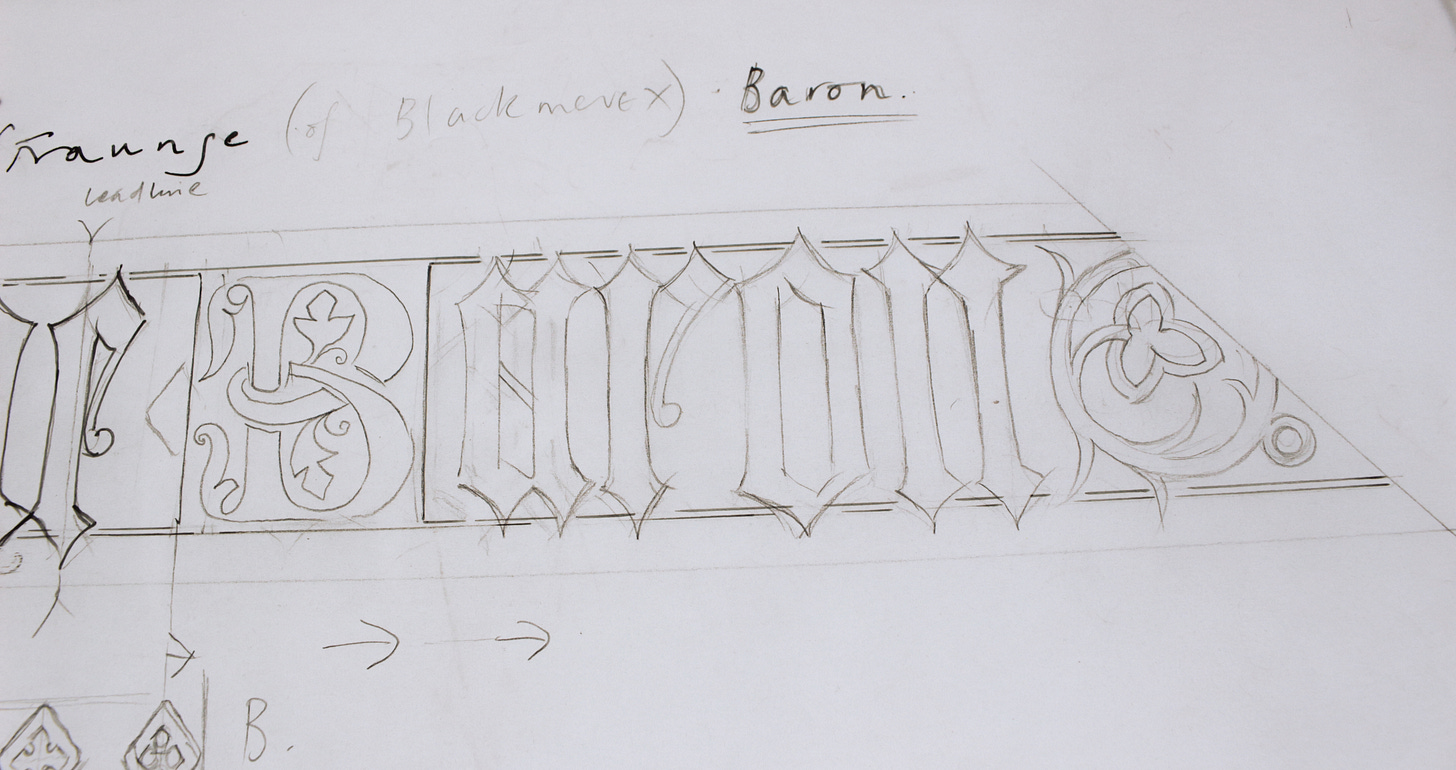

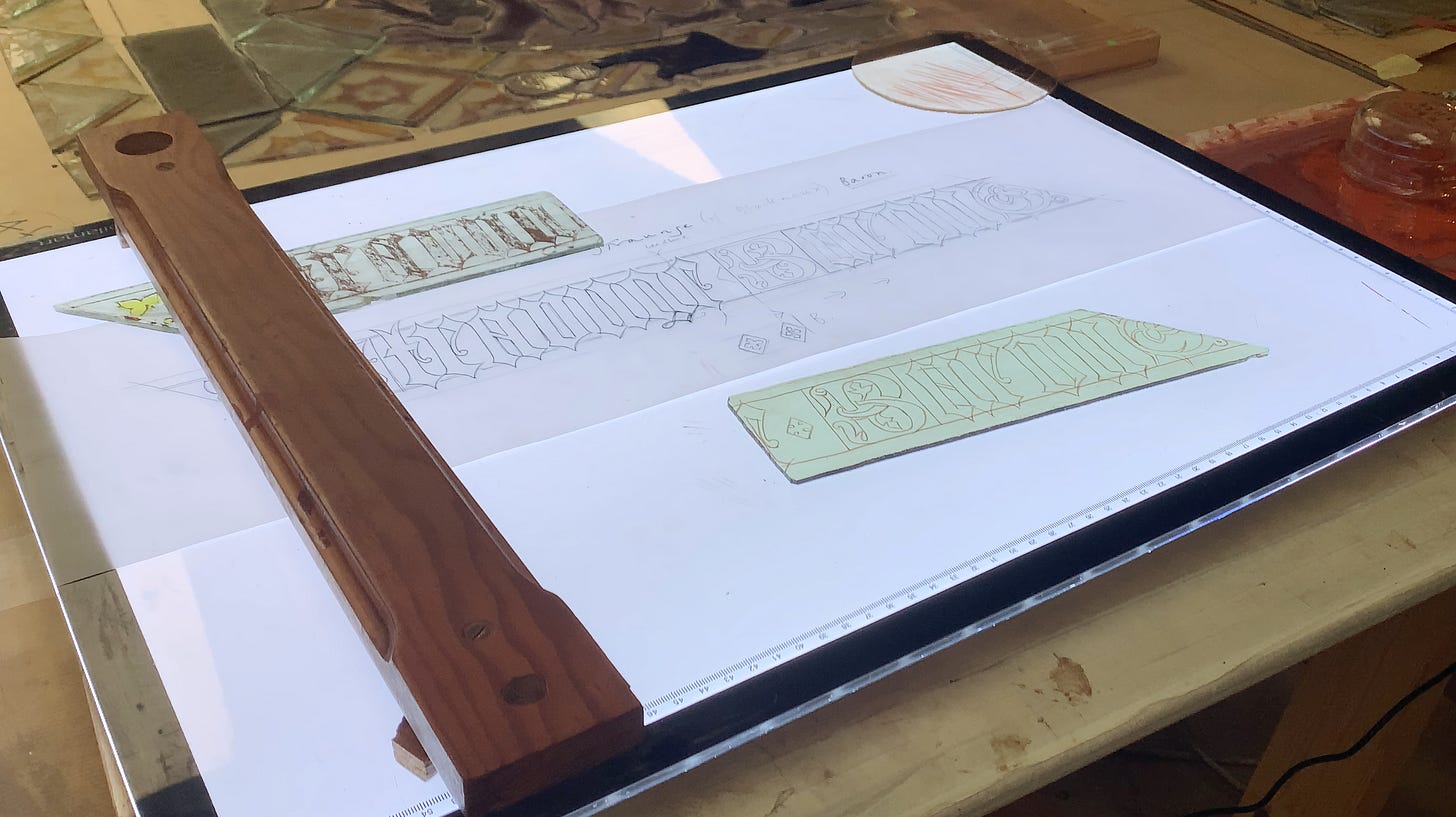

Back, now, to the dry and careful trace-lines — the continuation of the letter e, a decorative separator, then the word Baron:

Thus:

Now to fill in around the letter “B” and to flood inside the other letters. The “B”, being fiddly, requires the same fine-tipped brush as earlier was used to trace the outline:

The other letters, being more spacious, are perfect for the da Vinci series 5519, once you get the hang of how to load and use it (which — and here I know full well that I repeat myself — I promise you I’ll talk with you about some other time):

If you wish to watch an excerpt, certainly you may:

Thus:

Inevitably, and notwithstanding all the destruction that will soon be rained down upon this helpless piece that it might stand unnoticed by its ancient neighbour’s side, I am confident that your inner glass painter will be compelled to tidy up stray paint.

To which end, you’ll sometimes need a hard fine point:

Other times, a soft broad edge will do:

As you’ll see from the video, these two tools are but different ends of one:

It’s true, once the window is installed, no casual visitor will appreciate this cleaning that you devoted time to: the inscription is too high up and far away. But — and this is your reward though you be dead — future glass painters and restorers will see how you ignored all other tasks and pleasures so that your lettering might be neat and not exceed beyond the boundary of your trace-lines:

Now it’s time for the destruction, because you must distress your smooth and perfect paint to make it inconspicuous:

If one brush proves too soft, select another, and rain down further Hell upon your letters:

You’ll hear from the bangs and thumps that this task is not for the faint-hearted:

Thus:

Which surely gets us close — although stippling on its own, you realise, is not enough.

Therefore you now choose to soften the gummy paint with glycol, and distress the title further (which also leaves a whiff of tone in places — remember, I promised you there would be some):

Once fired …

… it will be time for silver stain: a topic I shall introduce when next I write to you about this project.

Fellow glass painters, I know that a large number of you will work alone. But you are not alone, nor ever will be, whilst you pursue this honourable and demanding craft. Your devotion is admired by vast unseen cohorts of departed craftsmen. And painters yet to come will value every well-wrought line and highlight that you bequeath them …

… especially when the care you take results in a perfection which only they will ever have the eye to notice.

Farewell and God’s speed until the next time that I write to you.

£260 — goodness me.

Lovely description of the thinking underlying his process. I hadn’t realized the research behind these ancient windows. Which makes me wonder. Why, when you restore, do you need to make everything look old again? Surely the elements will do that for you, as they did with the originals?

That £260 translates to nearly £36k today, which I guess would be a little bit more reasonable for all that work. I also note that I was born exactly 100 years after that bill was written - inconsequential in the scheme of things, but a rather nice coincidence all the same 😊

It’s very true about the meticulous processes and cleaning that conservators and restorers undertake, even on work that is so far away that it can barely be seen. Church ceilings come to mind - restoration work on a painted and gilded chancel ceiling 60 feet up between hammer beams is carried out as exactingly as if it could be inspected from a foot away on the floor below. We see everything we work on through a microscope (sometimes literally) and it all has to be as precise as we can make it. Even if nobody else ever sees it until the next conservation round, WE know it’s there and we take great pride in getting it right. We can never be ‘it’ll do’ jockeys!